Historical subjects

THE 16 FORTS OF THE FORTIFIED POSITION OF LIÈGE (F.P.L.)

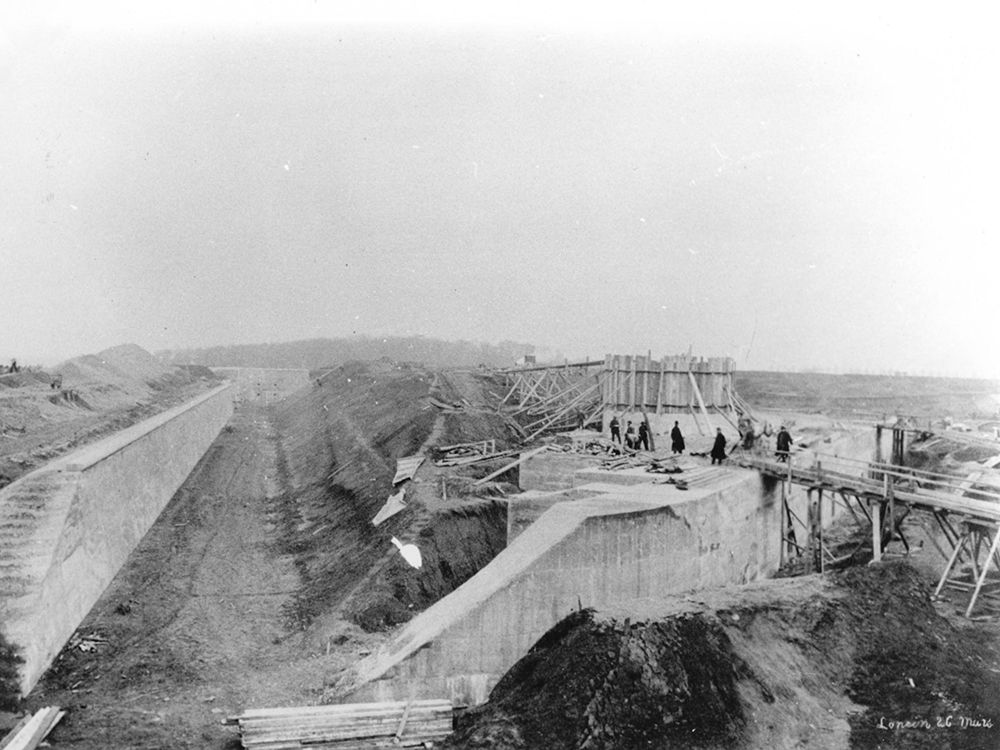

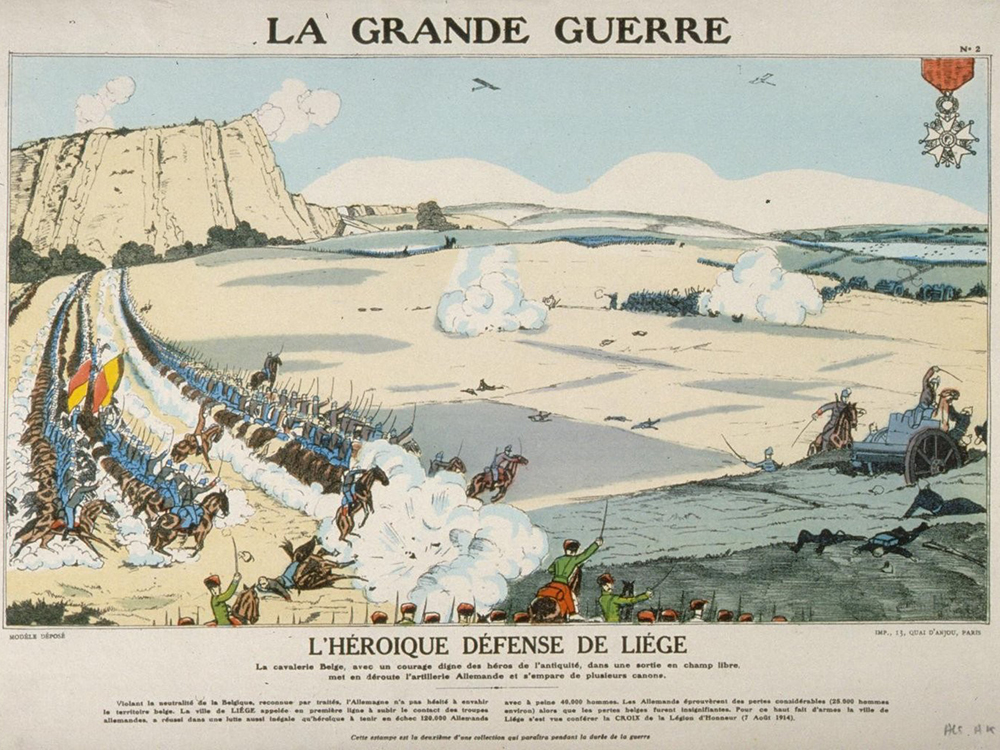

The F.P.L. was a defensive belt of fortifications surrounding Liège, including 16 forts built with massive amounts of concrete, sited partially underground. Distances between forts were such as to enable them to provide covering fire for their neighbours. They also protected the city of Liège and its main bridges. The heroic resistance of Belgian forces in these positions at the start of WW1 (4th to 16th August 1914), had a decisive influence in the war’s early stages by giving French troops extra time to prepare. Meantime, the forts were being pummelled by the first shells from ‘Big Bertha’. To commemorate this feat of arms, Liège was the first non-French town to be awarded the French Legion of Honour. Furthermore, as another mark of recognition of the city’s courage, it was chosen to host the unique symbol that is the Interallied memorial. During the Second World War, this belt remained operational, with 4 new forts being added to it.

One last honour – and certainly not the least: Paris cafés changed the name of a popular dessert from café viennois (Viennese café – which had connotations with one of the enemy powers) to café liegeois, which is popular all over the so-called ‘Ardent city’ (Cité ardente).

After the taking of the PFL on 16th August 1914, the Kaiser’s troops carried out a turning manoeuvre in the Sambre and Meuse river valleys between Dinant and Charleroi and to the north of the industrial backbone of Belgium. By the end of August, the epicentre of military operations on the Western Front had shifted towards the French-Belgian border.

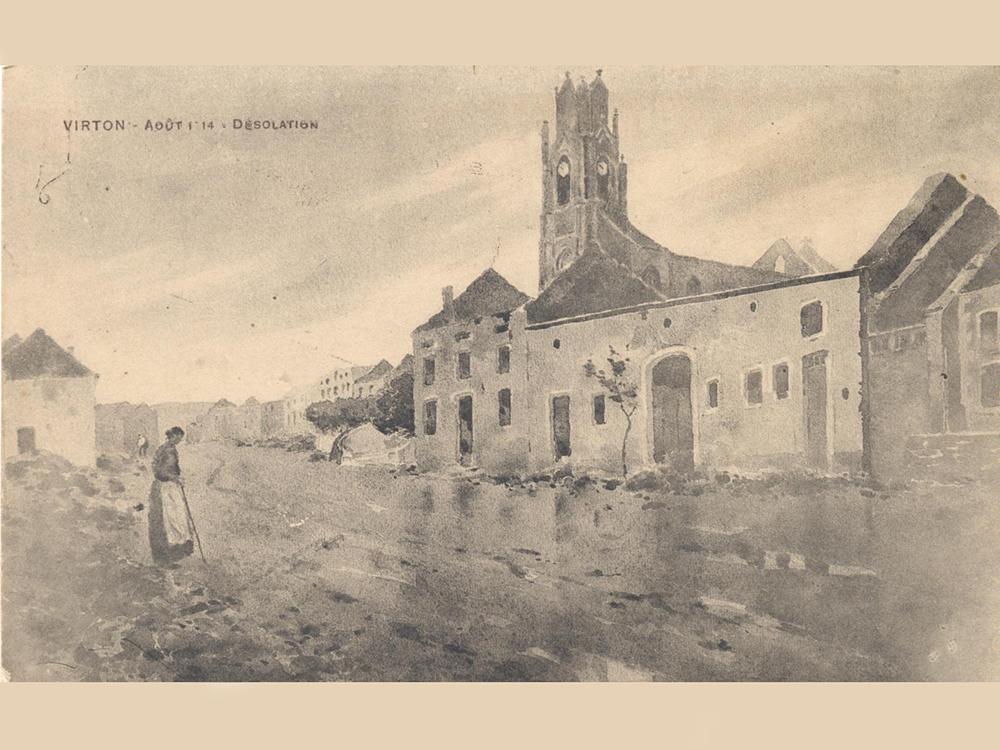

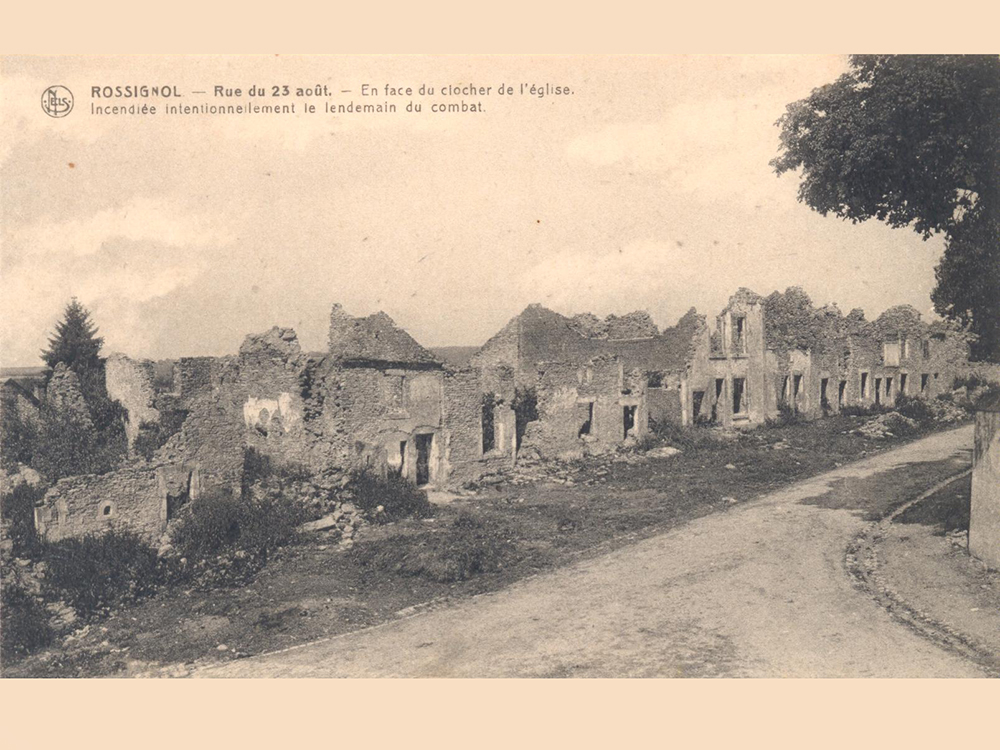

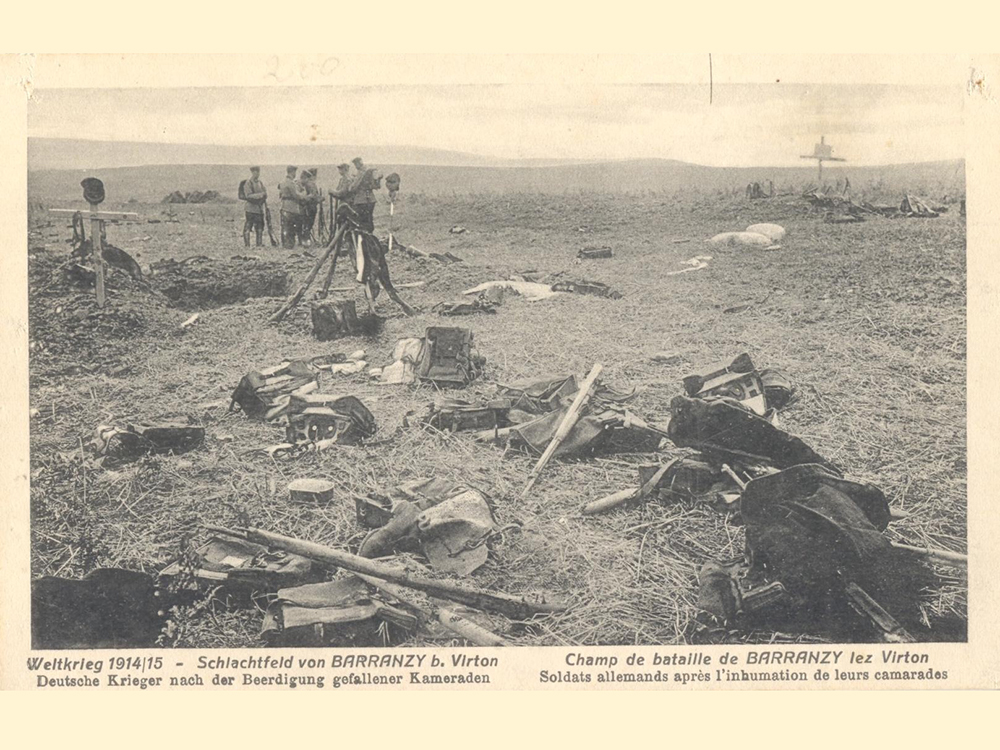

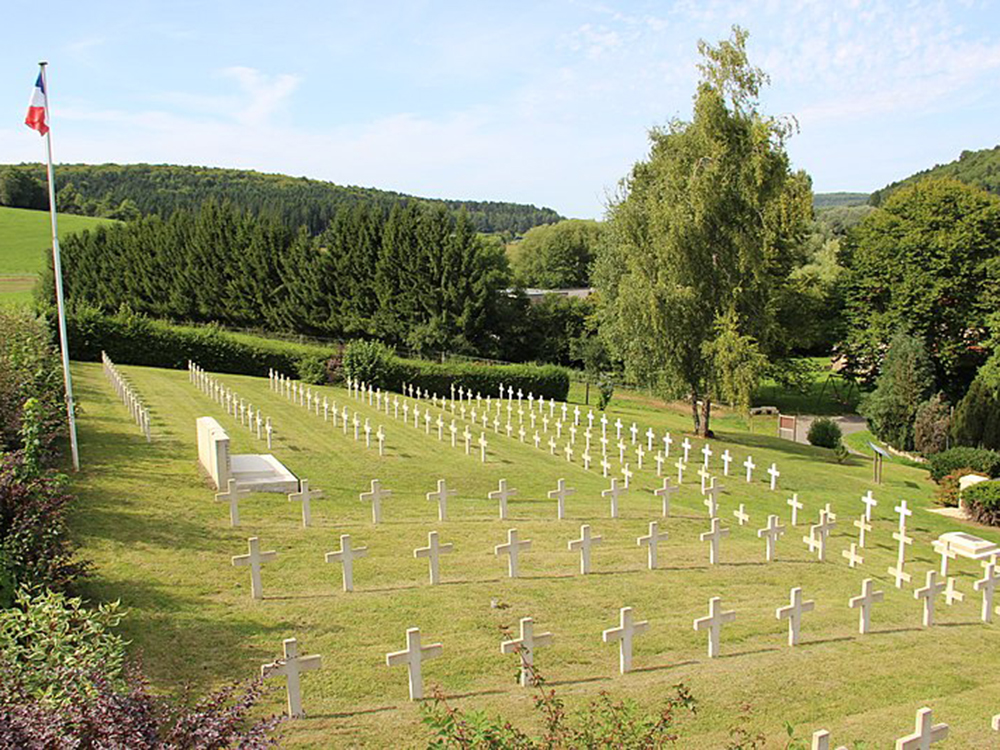

This is the Battle of the Frontiers. Dug in on the heights above the Sambre river, the French 5th Army tries to block the enemy’s assaults, while the 3rd and 4th Armies in Lorraine and the Ardennes clash with the Germans in 15 bloody battles from Mercy to Maissin. On one day alone, the 22nd August, in Belgian Luxembourg, it’s estimated that combined French and German casualties were 67,508 (not forgetting almost 1,000 civilian casualties). Following defeat in the Ardennes and the crossing of the Meuse river by the Germans at Dinant, the French Army has to pull back a full 300 km to the south, halting on the banks of the Marne.

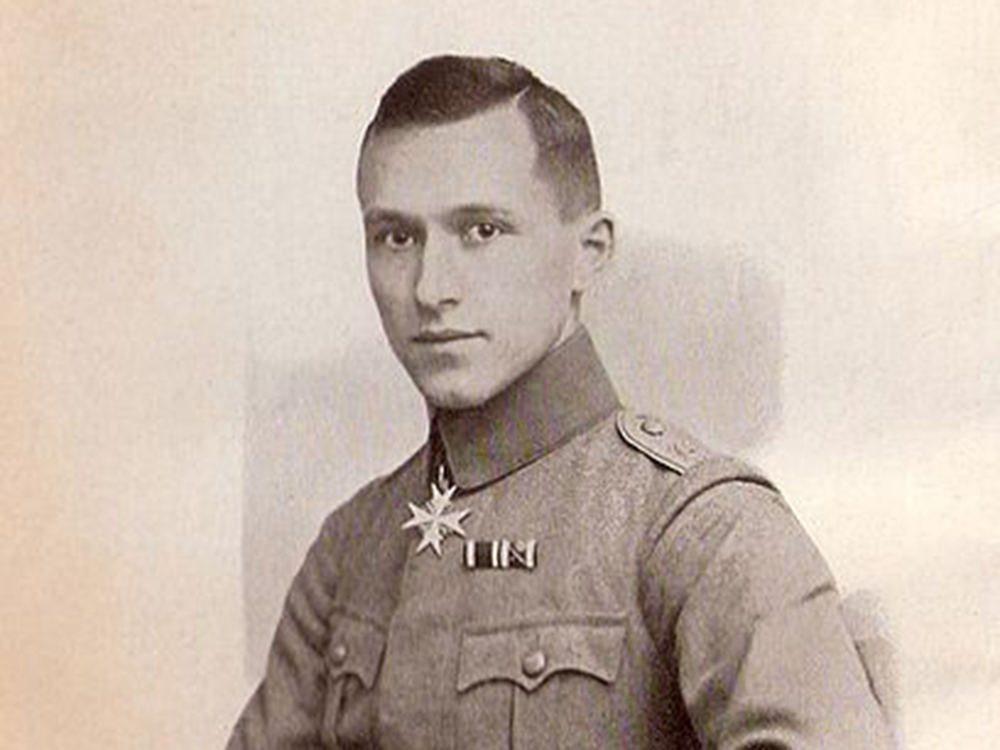

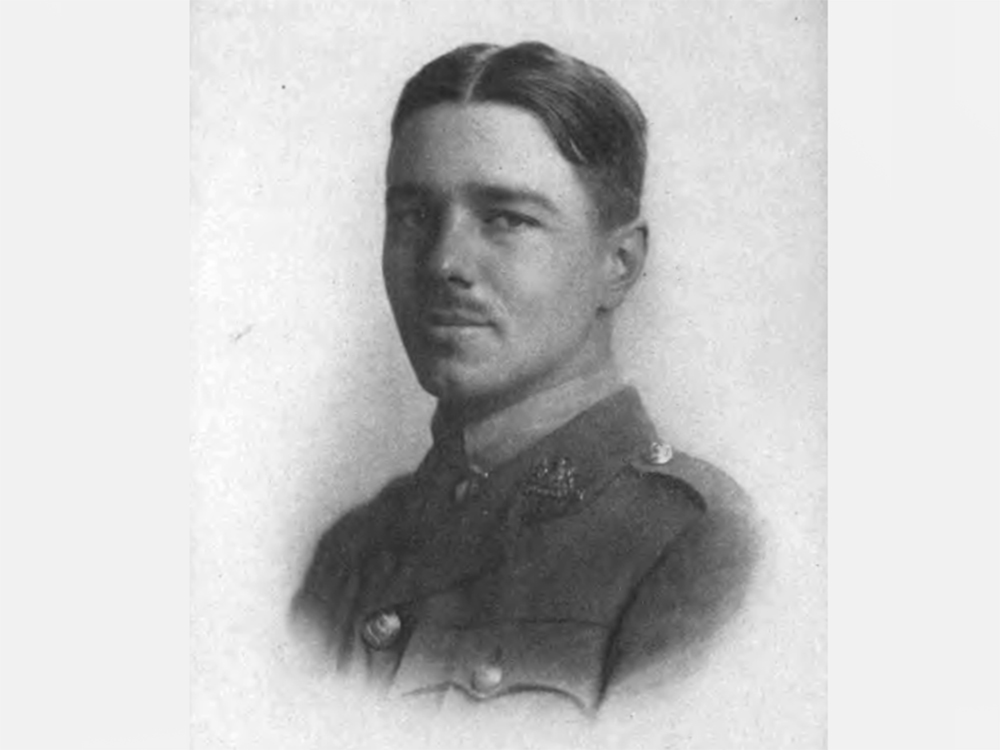

Many writers took part in the Great War (with many killed in action), including Alain-Fournier, Jean Giono, Charles Péguy, Maurice Genevoix and Louis Pergaud on the French side, Edlef Köppen, Ernst Jünger and Gottfried Benn on the German side and English poet Wilfred Owen.

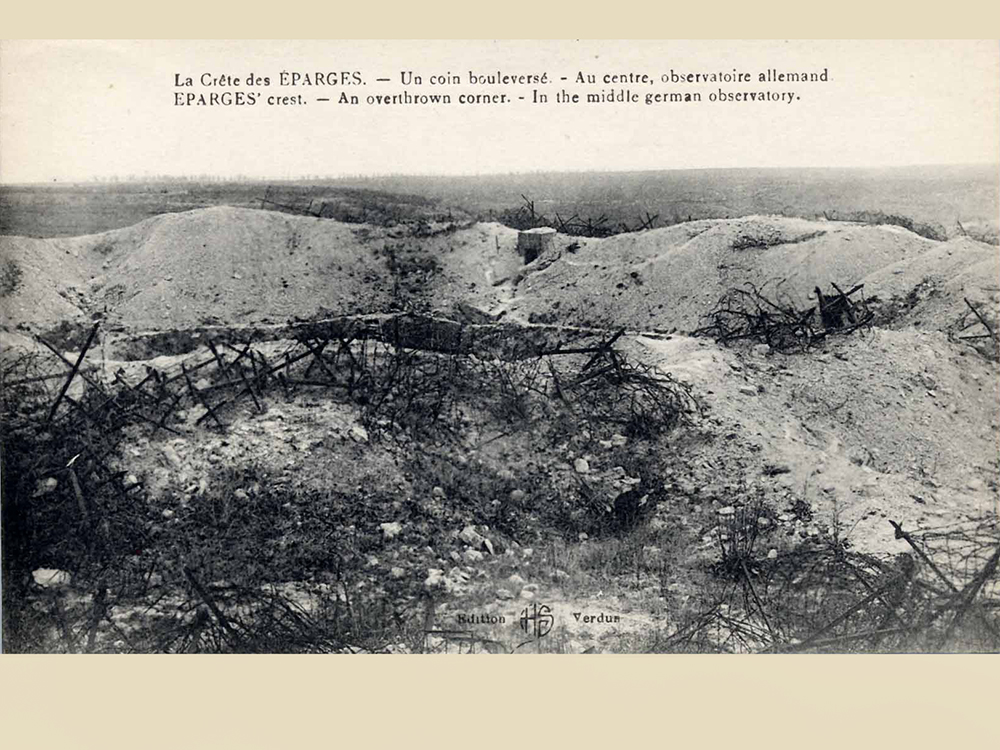

Several memorials dedicated to these authors exist in the Verdun area, near the village of Saint-Rémy-la-Calonne and on the Crête des Eparges ridge. The writer Psichari, a friend of Péguy and son of one of the founders of the French Human Rights League and a passionate supporter of Dreyfus, died in the Battle of the Frontiers in Rossignol.

The duration of the First World War, Belgium was one of the most critical sources of military intelligence and a hot-bed of espionage activity.

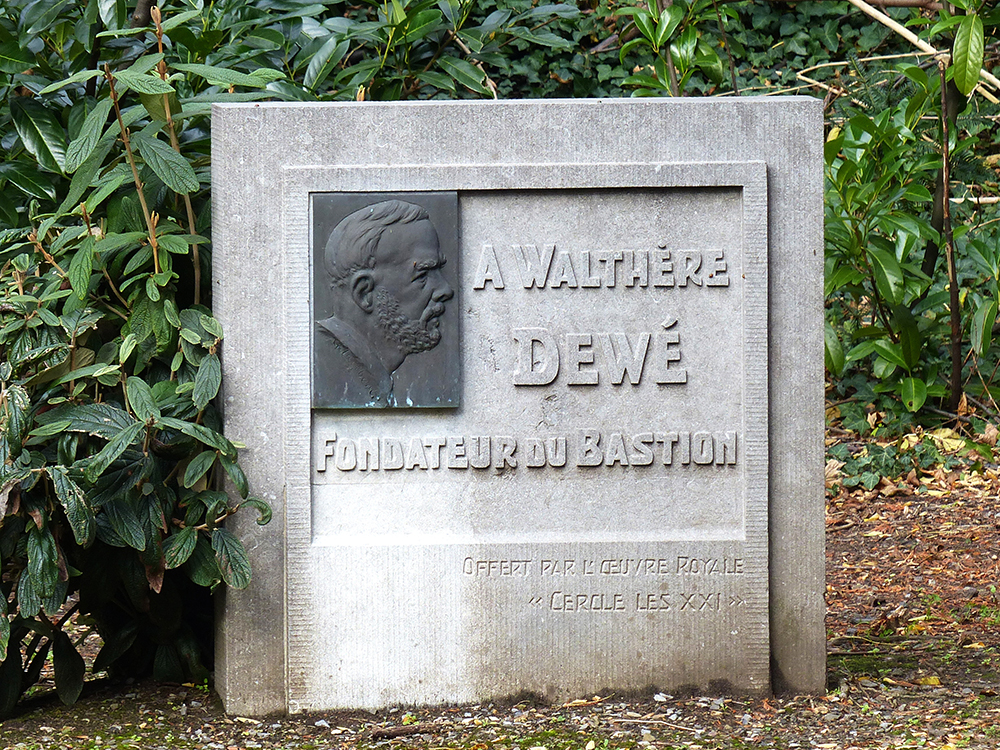

Founded in 1916 by citizens of Liège, including a Jesuit from the Collège St-Servais (Père Desonay) and two engineers (Walthère Dewé and Herman Chauvin), who were immediately joined by the local chief of police, Commissaire Neujean. By the end of the war, the Dame Blanche network boasted almost 1,000 agents.

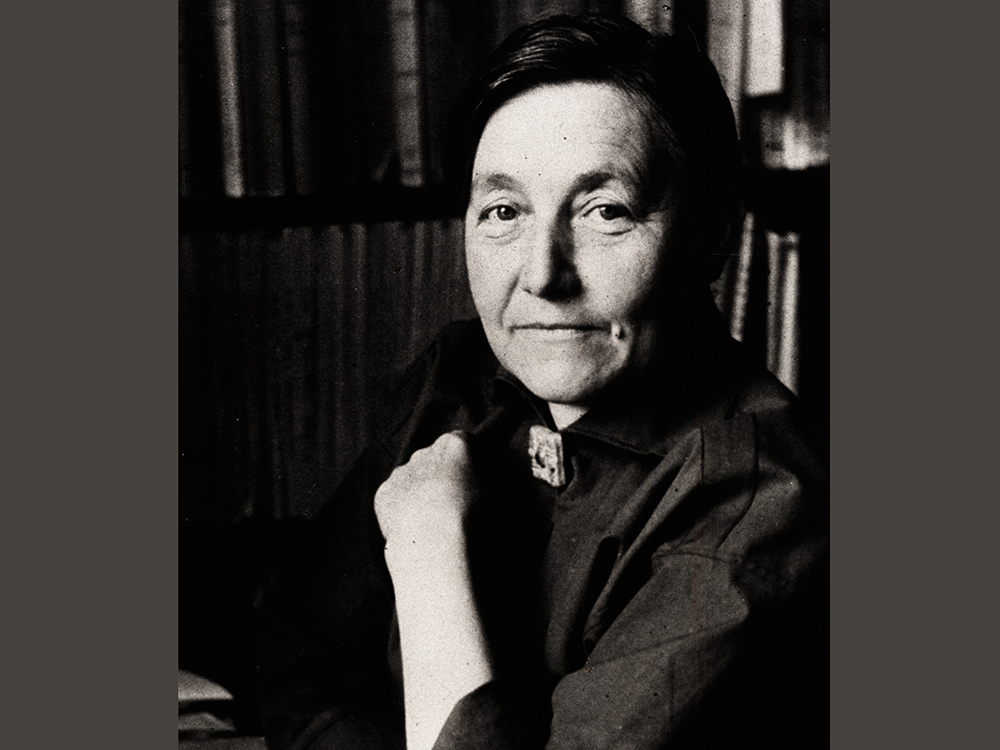

This highly-organized network included many women amongst its members, 30% of the total, including some in the higher echelons, like the brilliant Marie Delcourt, who later became a professor at the University of Liège and a supporter of the League of Nations. The network spread all over Belgium, the north of France and the Grand-Duchy of Luxembourg.

It was so effective that the British War Office said that it supplied three-quarters of all useable intelligence relating to these geographical areas. Of its 128-strong ruling council, 50 were women. Marie Delcourt was involved in the Resistance right from the start. She was made an Officer of the Order of the British Empire for her work. Marie Delcourt was active from the 1930s onwards in campaigning for the vote for women and greater equality in the workplace.

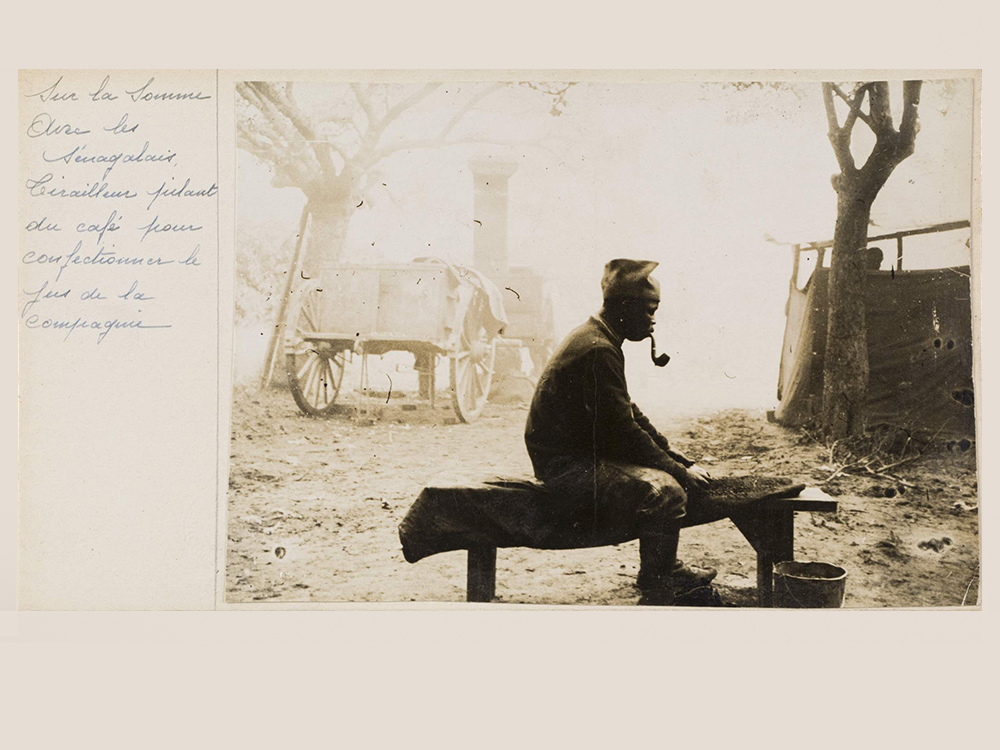

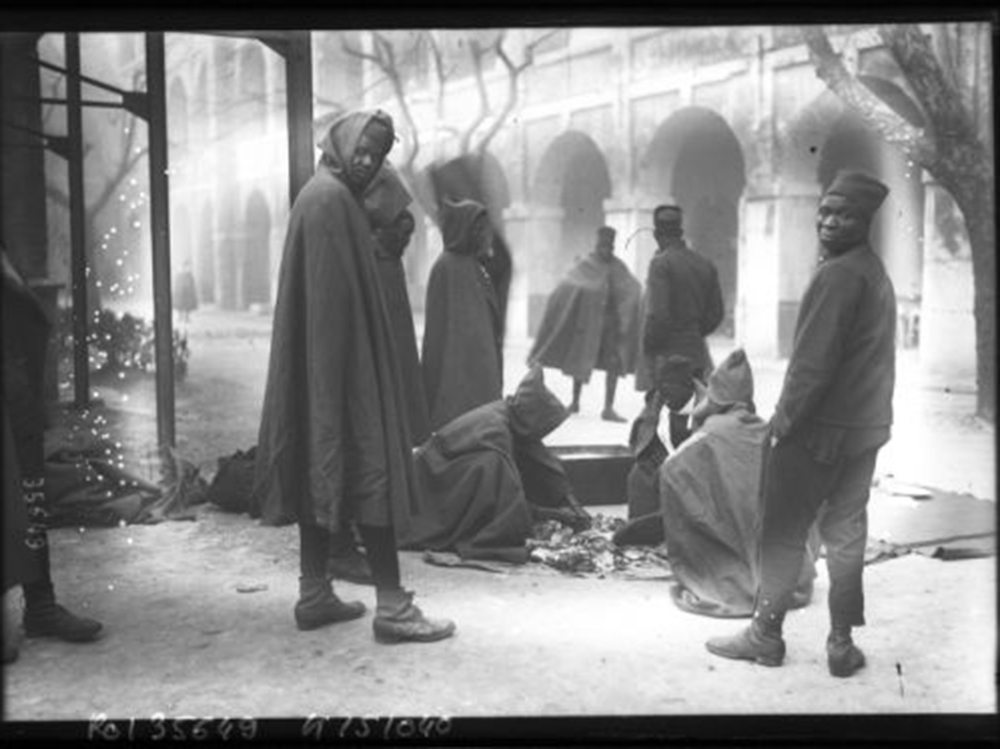

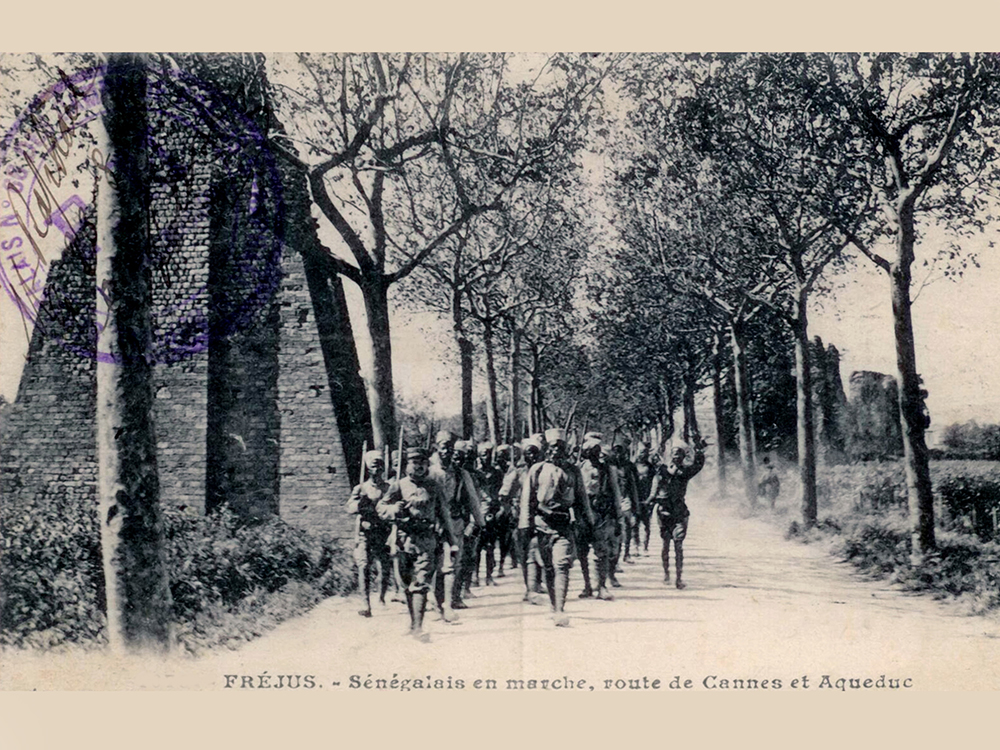

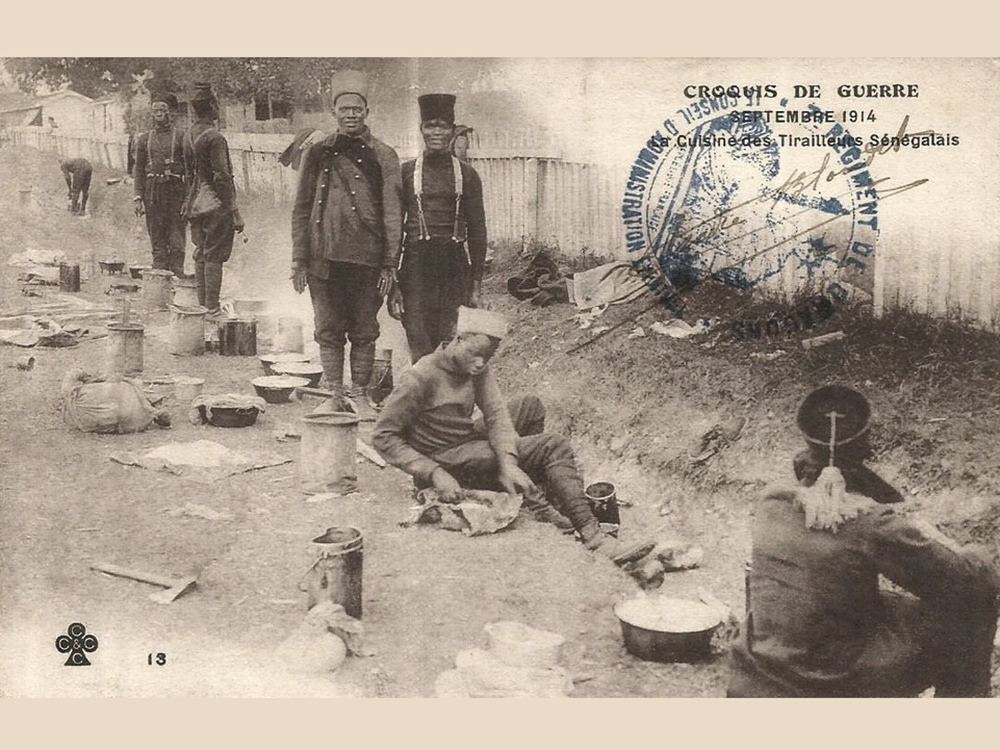

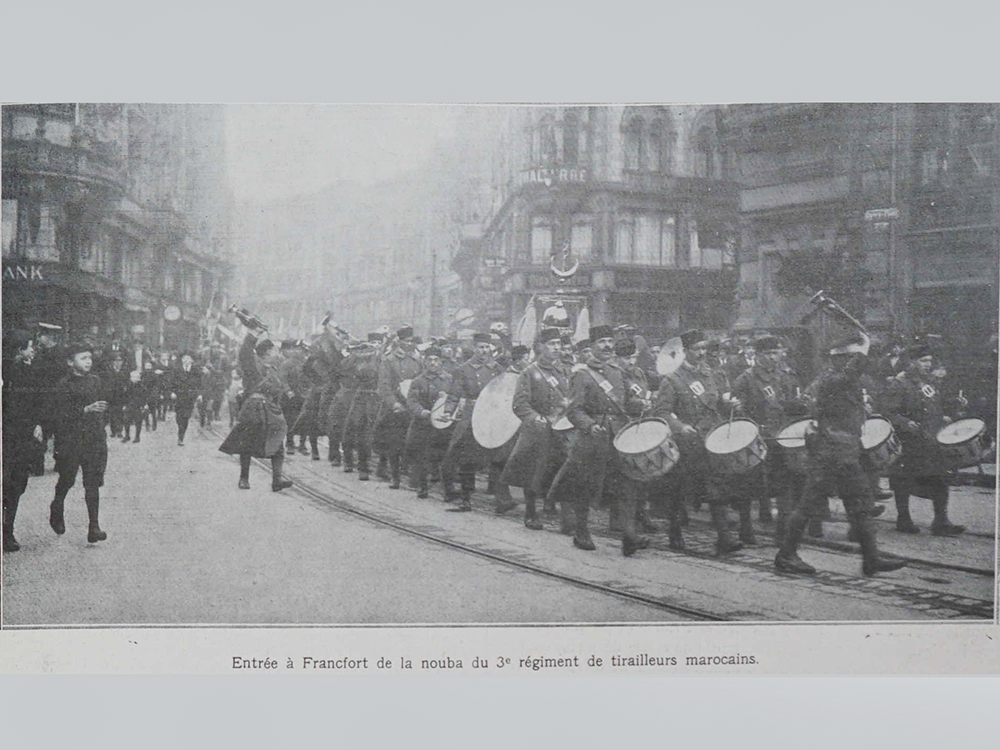

During WW1, almost 200,000 ‘Senegalese’ from French West Africa fought under French colours, more than 135,000 doing so in Europe, most notably in the Battle of the Yser, at Verdun, on the Somme (1916) and the Aisne (1917). Around 15% of the total, 30,000 soldiers, were killed, and many returned home wounded or permanently disabled.

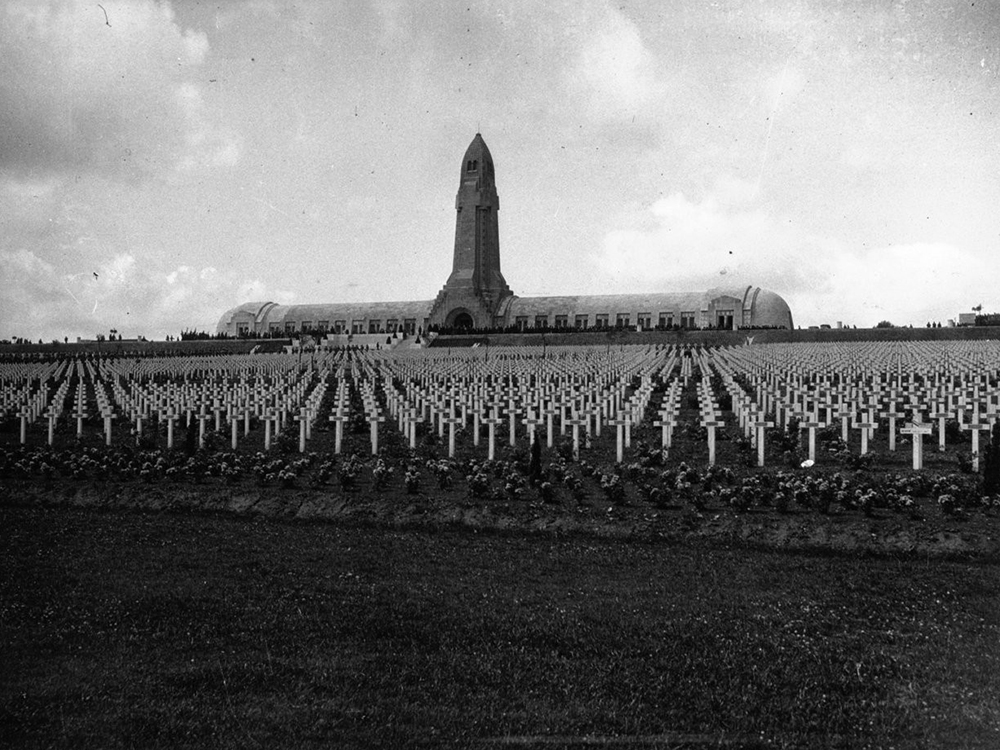

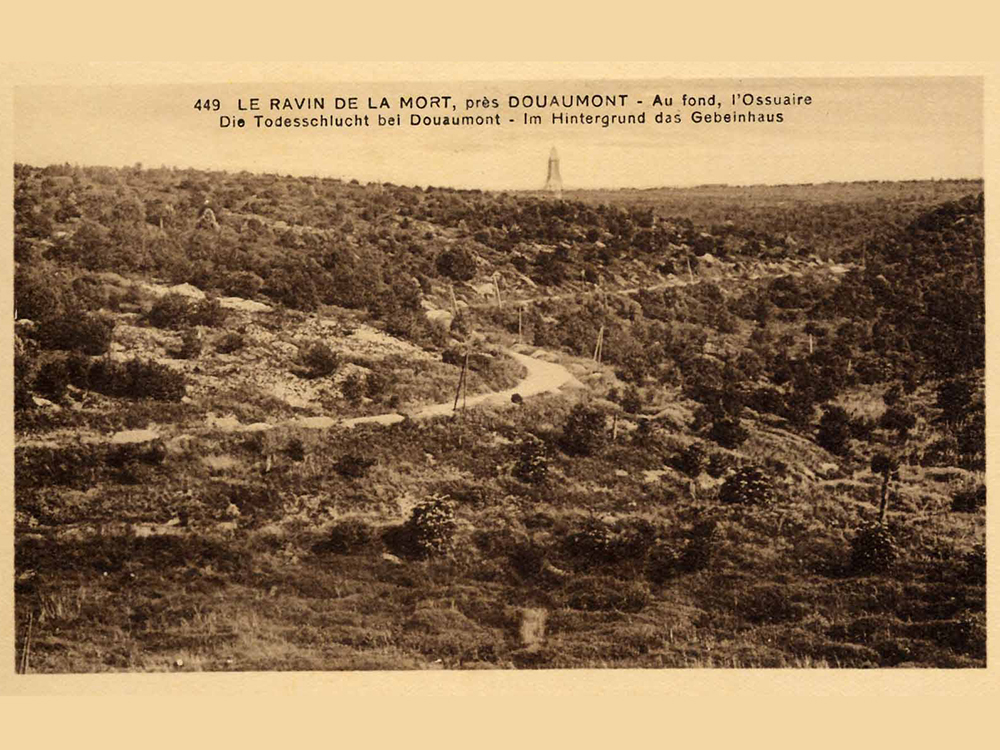

Facing the Douaumont ossuary, a monument built to commemorate those who fought in the Battle of Verdun in 1916, is the main cemetery at Douaumont, where 16,142 French soldiers lie. A section contains 592 Muslim headstones with a nearby monument built in the Islamic style which is dedicated to the memory of these soldiers.

To the west of the cemetery is another monument depicting the tablets of the Law, which commemorates the role of Jewish soldiers.

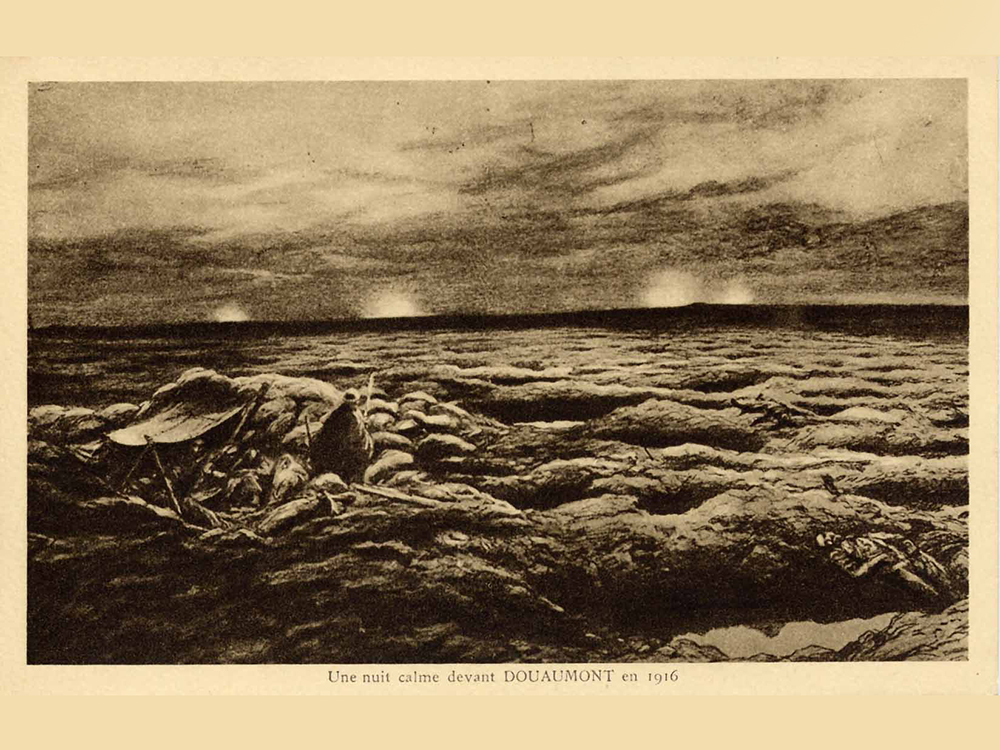

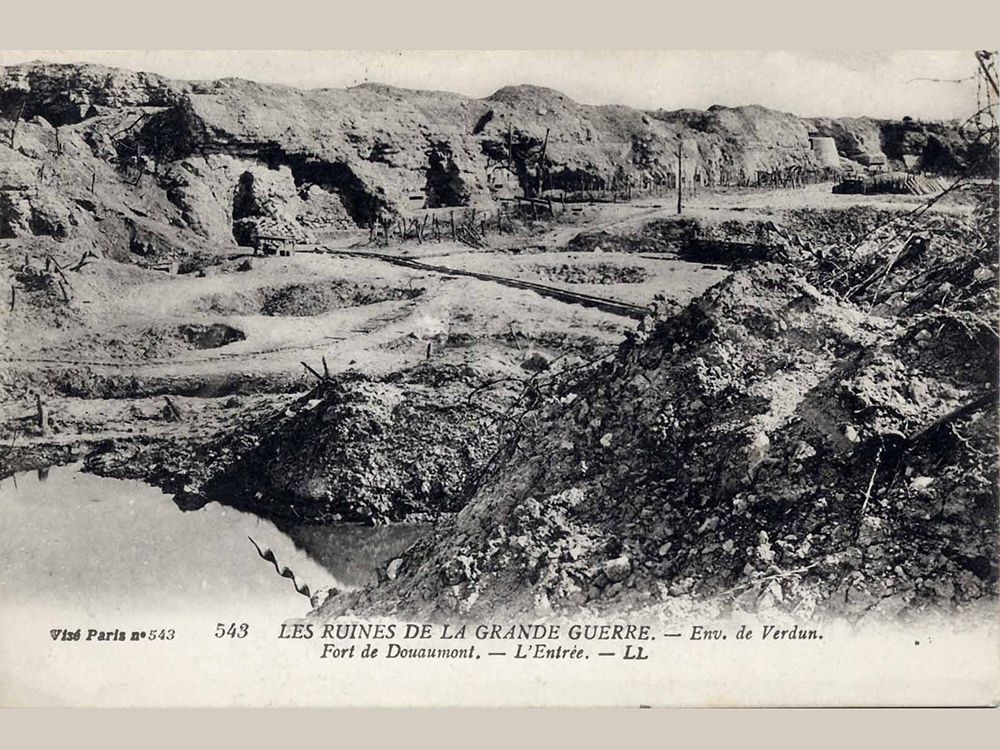

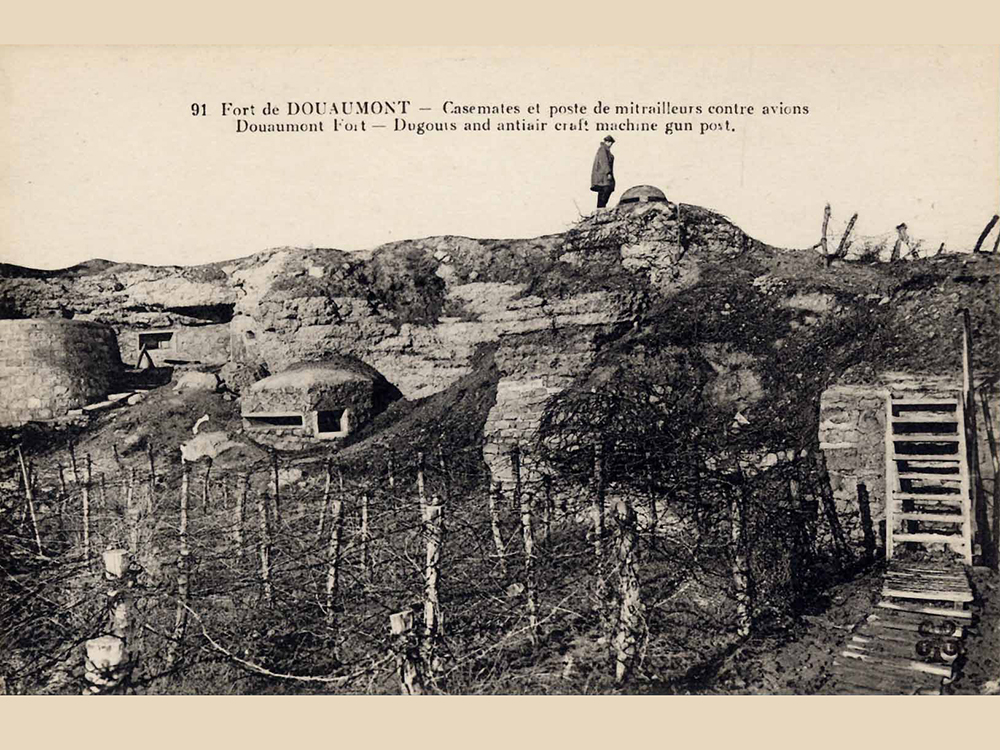

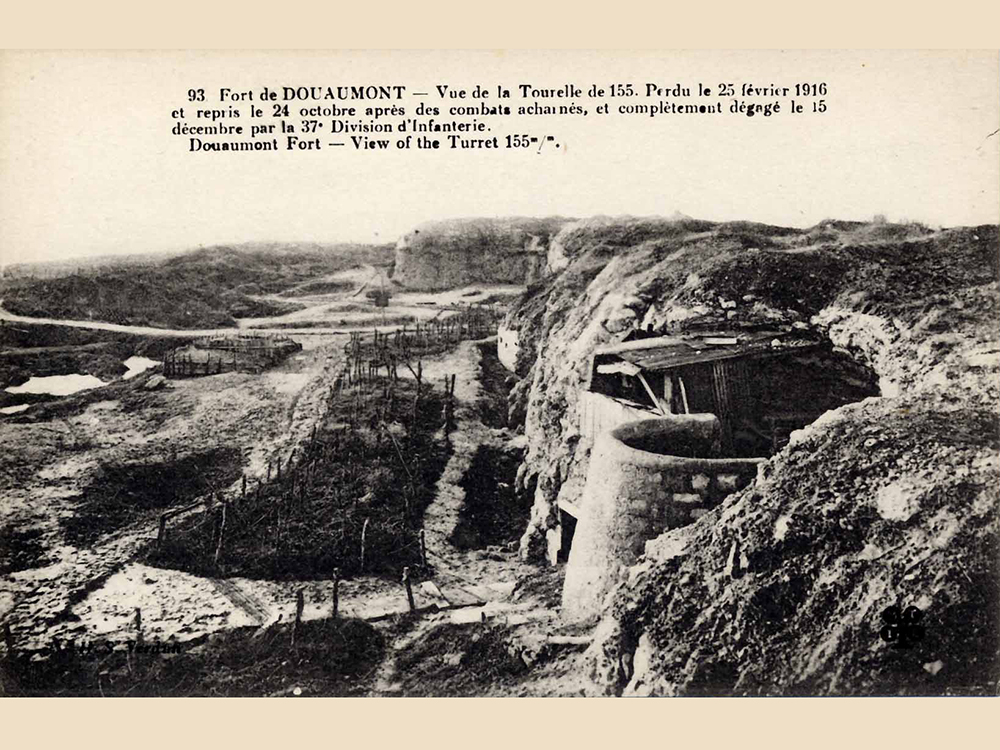

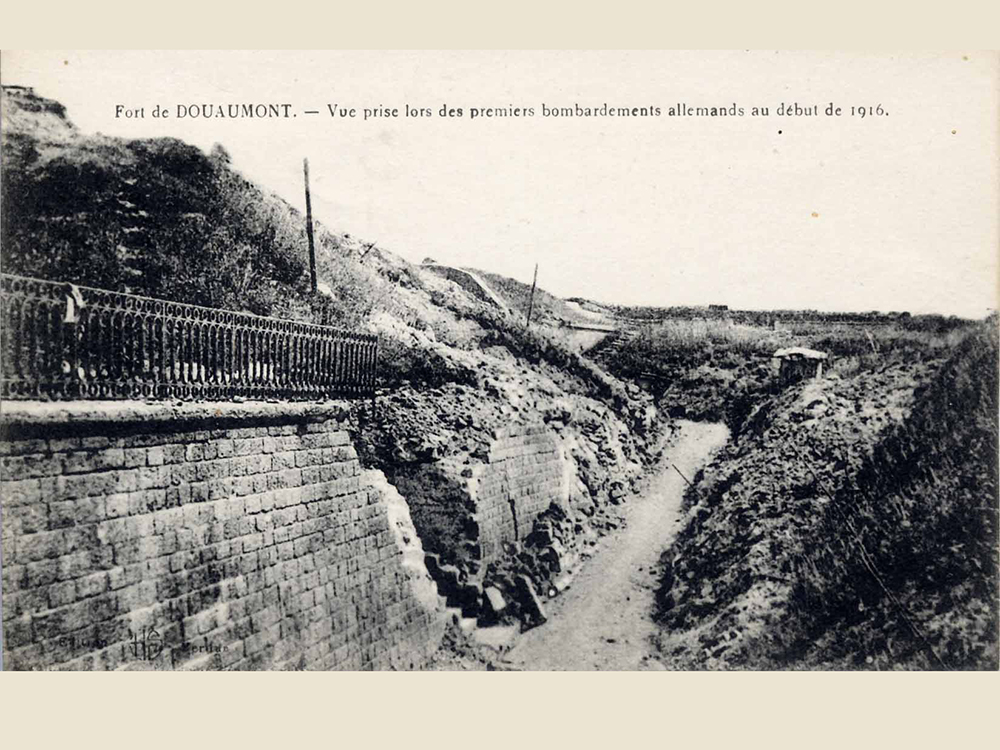

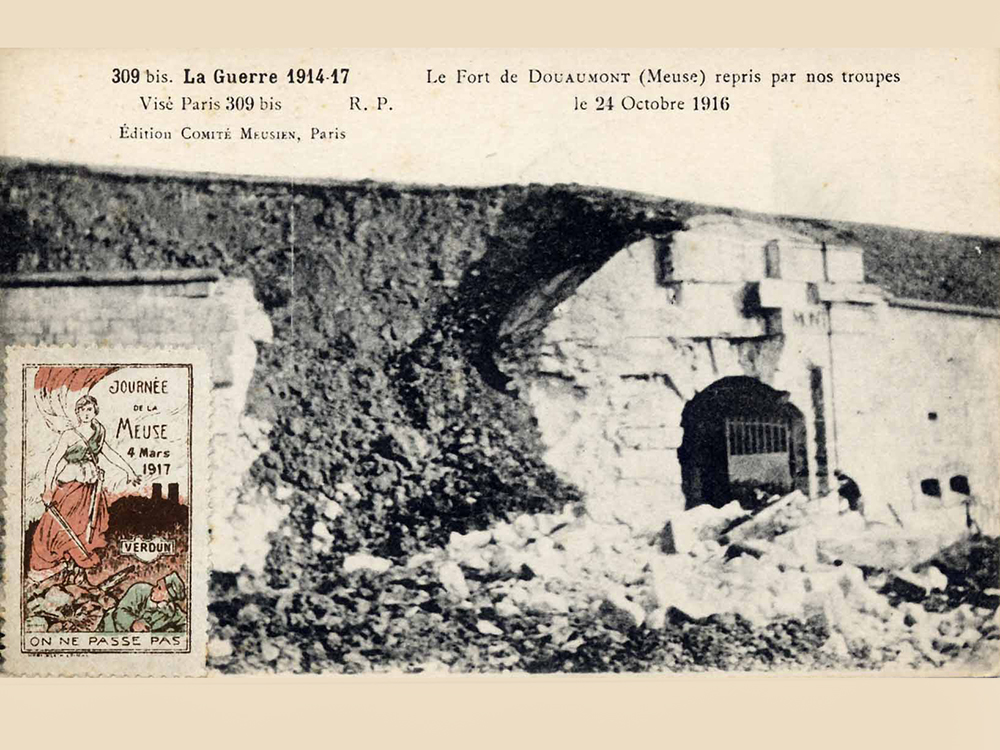

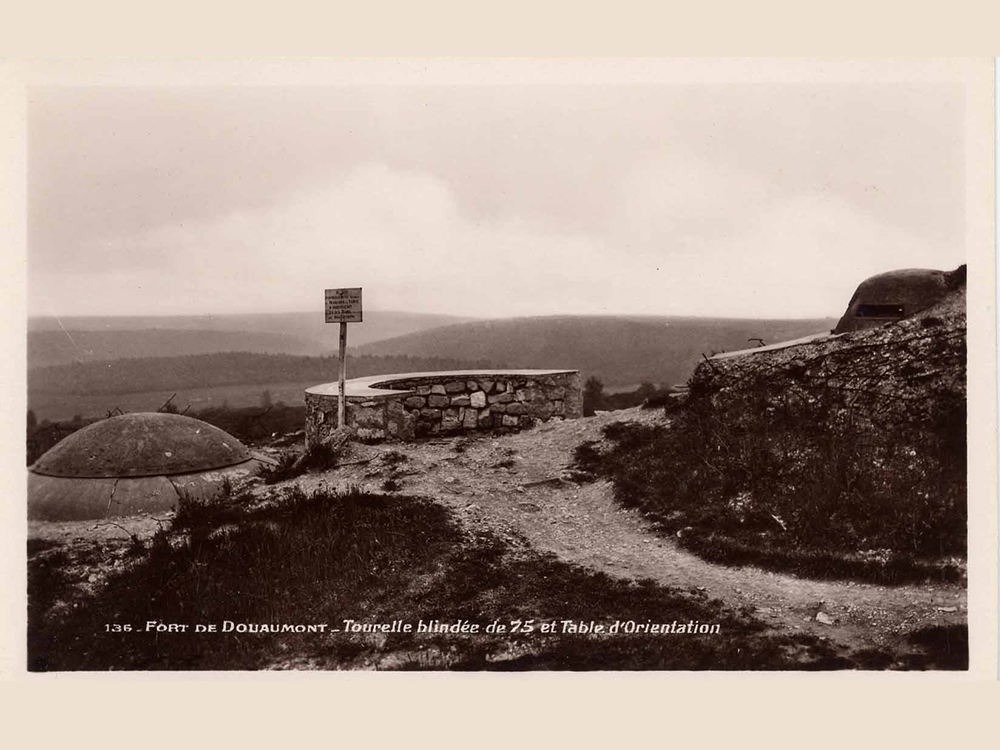

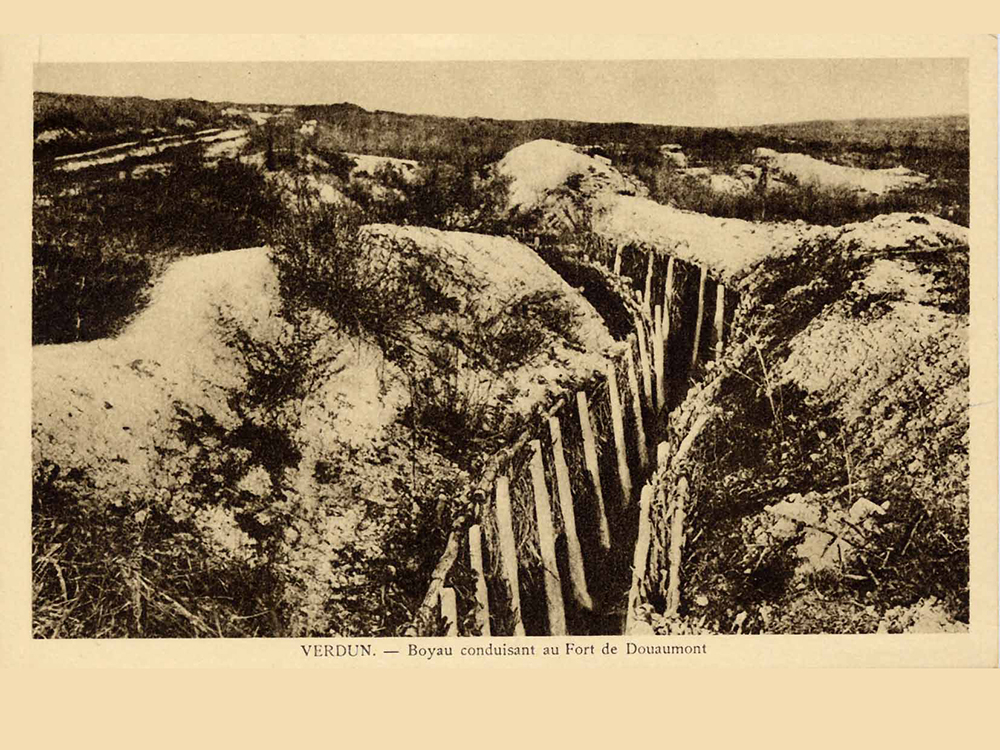

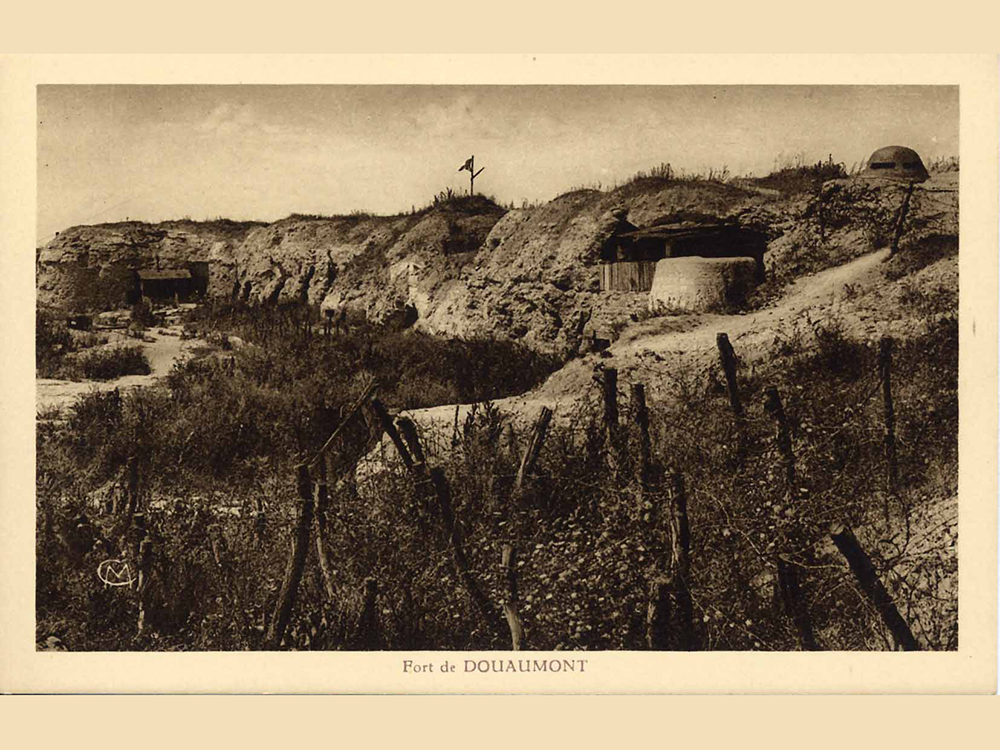

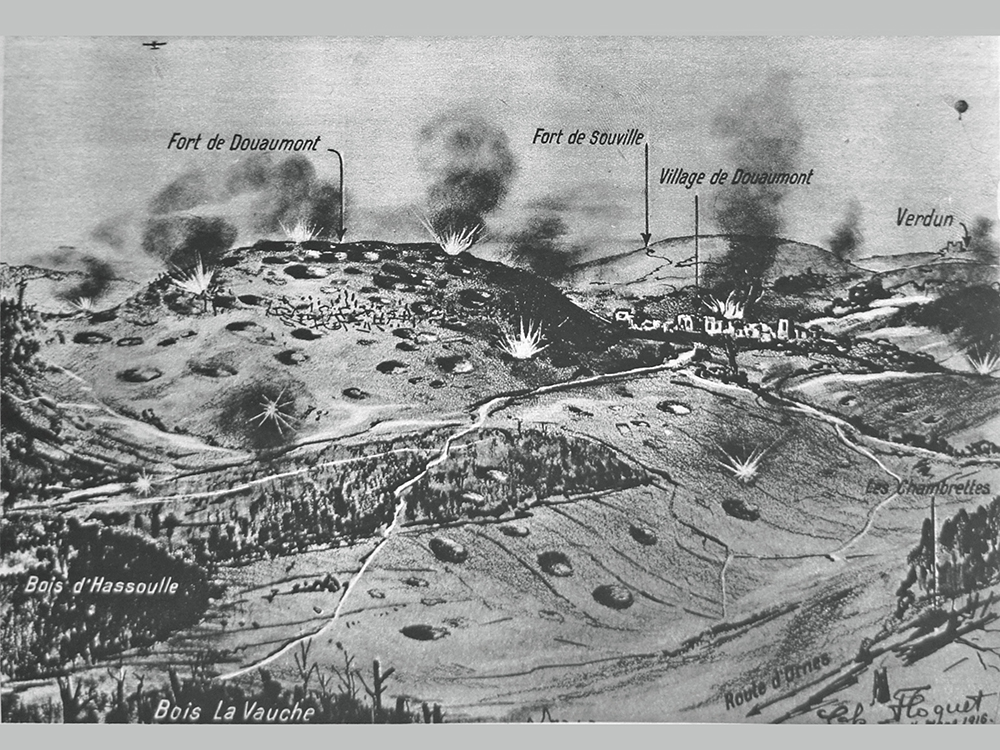

The strongest fortification in the entire complex was Douaumont Fort, taken by the Germans in February 1916 at the very start of the Battle of Verdun. It was occupied by the Germans for 8 months, being used as a staging area for their offensives. Despite several attempts to take it back, the fort was not recaptured until 24th October 1916.

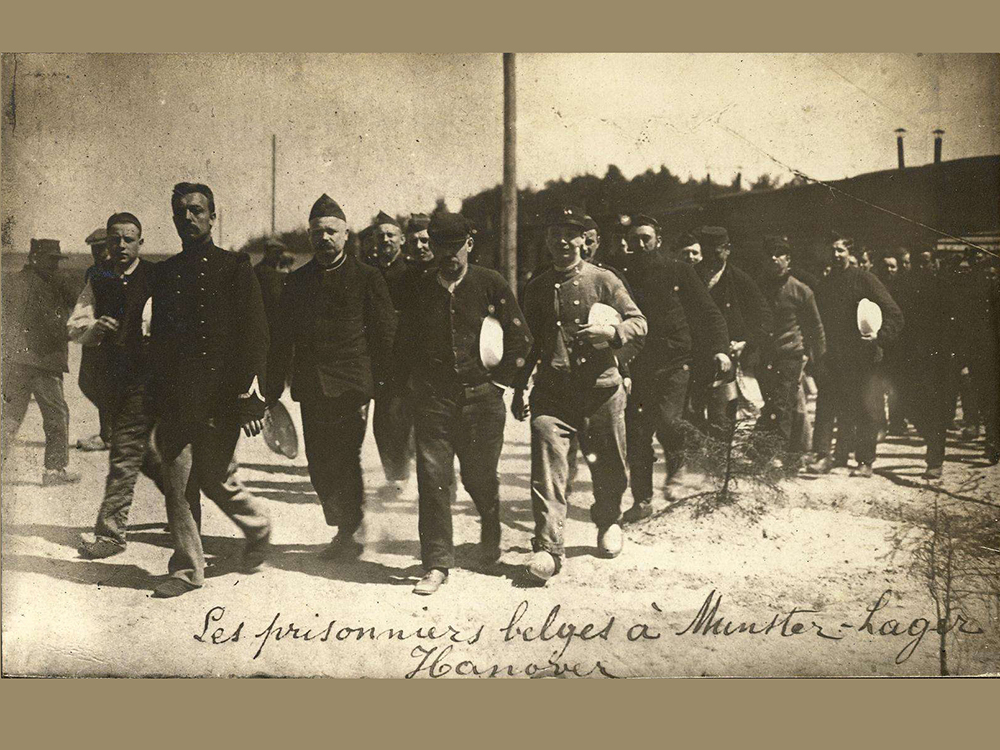

PRISONERS OF WAR (POW)

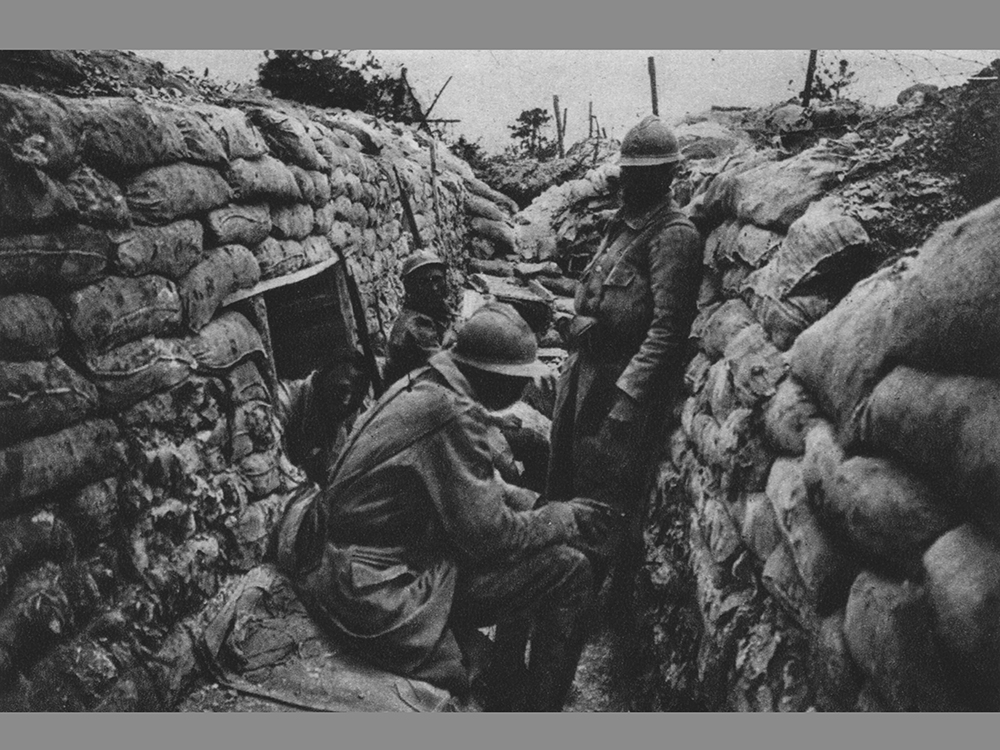

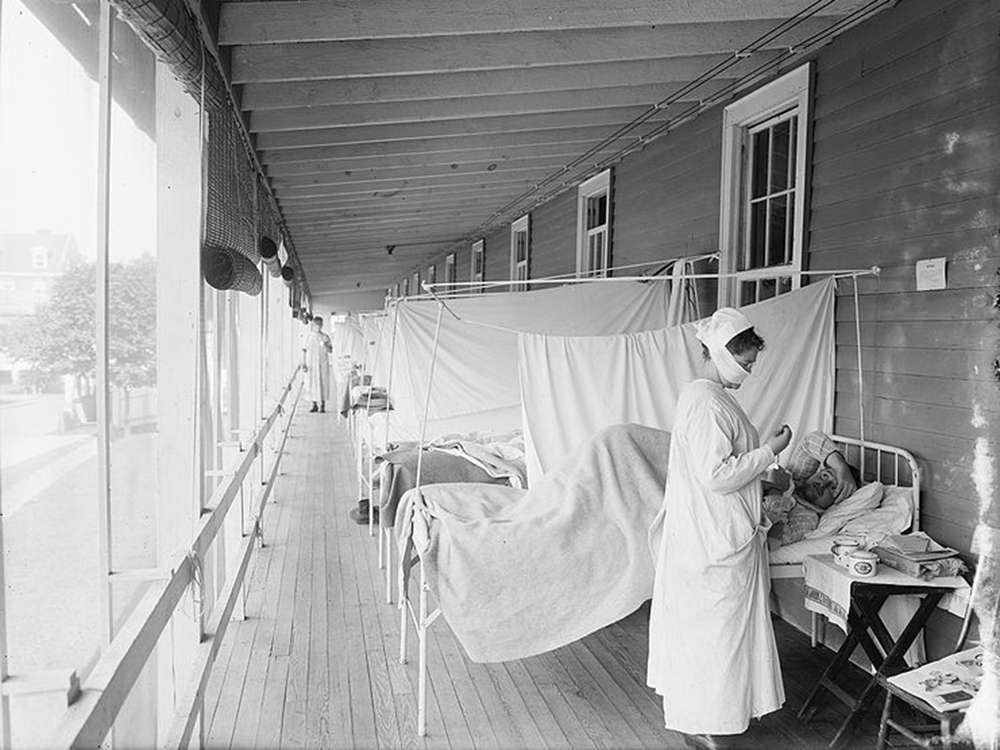

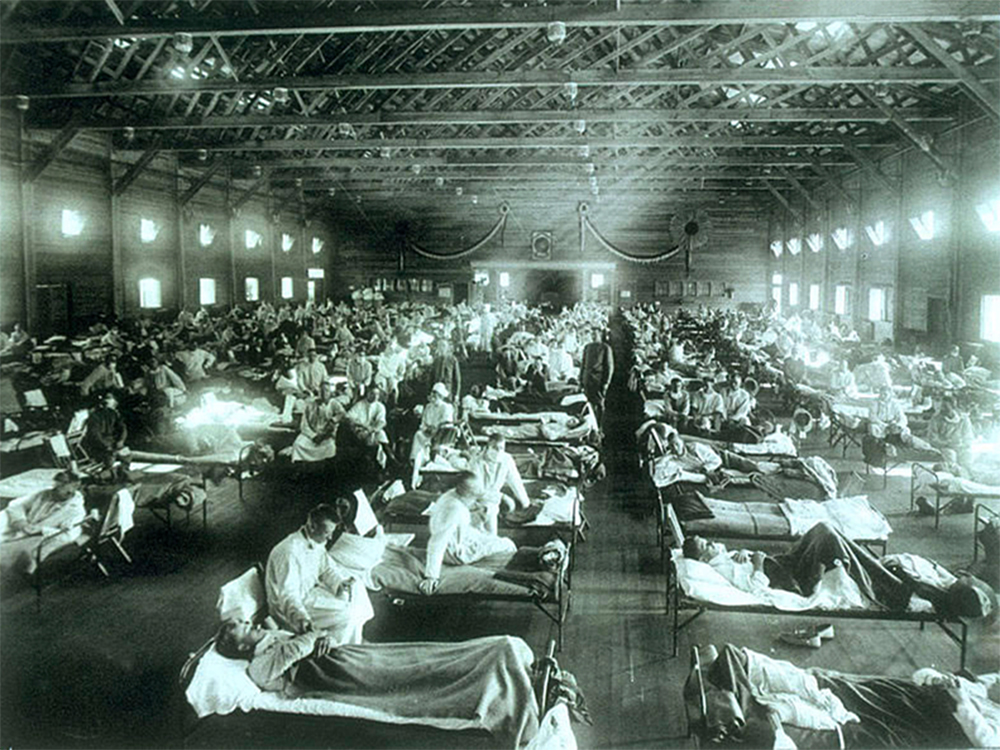

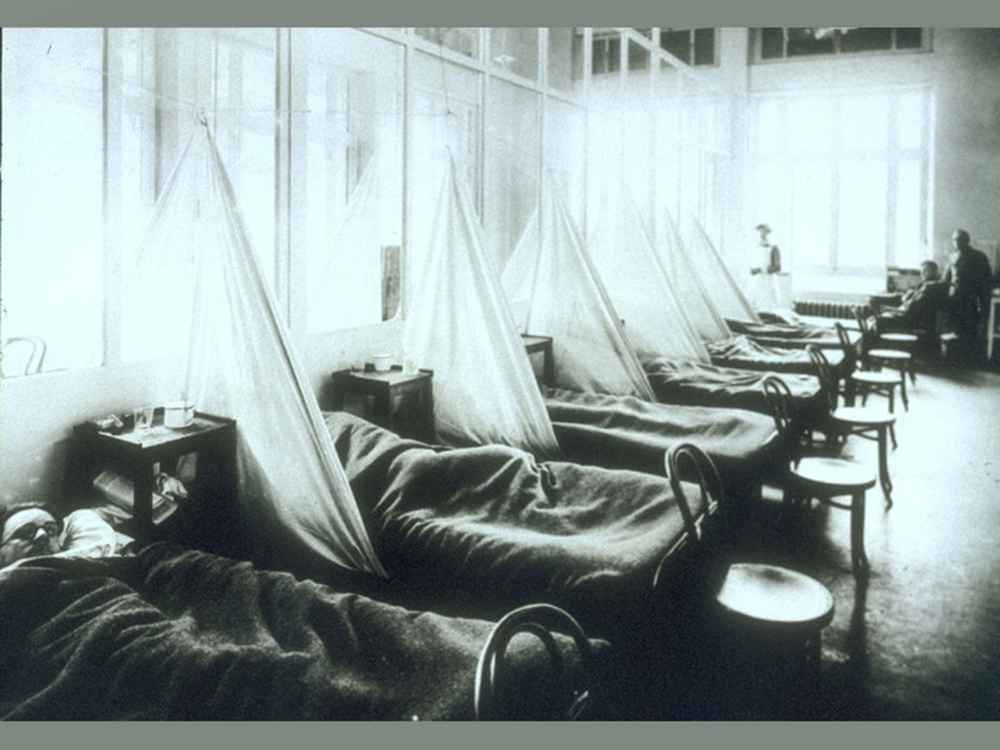

It’s estimated there were some 7 million prisoners taken during the First World War, around 2.4 million of whom were captured by the Germans. Right from the start of the war, the German general staff was taken by surprise at the number of prisoners captured (125,000 French troops during September 1914). POW camps were set up from 1915 onwards (almost 300 in total). Some of these were located in northern and eastern France.

Cold, hunger, disease, ill-treatment…the conditions in which hundreds of thousands of prisoners were held were very tough. The camps housed soldiers from many armies – French, Russian, British, Belgian, American, Canadian, Italian and more – as well as individuals from a wide variety of social backgrounds (workers, farmers, civil servants, intellectuals, etc).

More information:

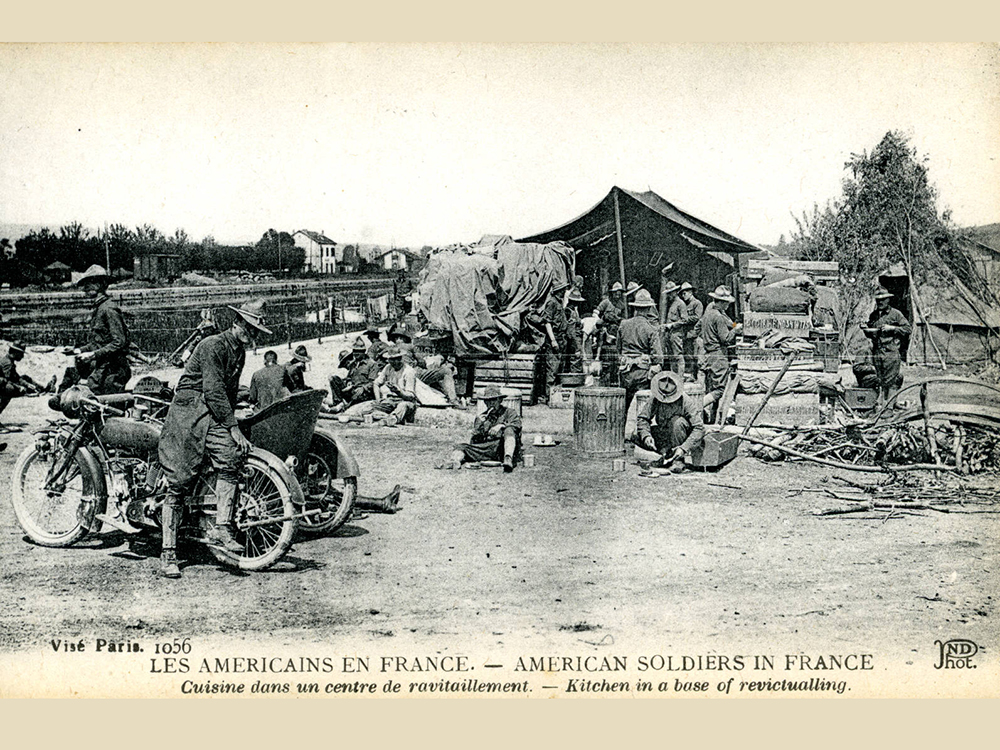

The Meuse area saw the biggest US military operation of the First World War. The first action was the reduction of the Saint-Mihiel salient, which took place between 12th and 16th September 1918. Some 216,000 doughboys and 48,000 ‘poilus’ (the nickname for French infantrymen), supported by 3,000 artillery pieces, more than 1,400 aircraft and 300 tanks, pushed back the 60,000 Germans and Austro-Hungarians occupying this section of the front. Although a genuine breakthrough was achieved, it was made easier by the fact the German army was already retreating. US troops captured 15,000 prisoners, 750 machine guns and 443 artillery pieces. They suffered 7,000 casualties.

The second operation was known as the Meuse-Argonne Offensive, which took place from 26th September to 11th November 1918. 400,000 US soldiers supported by 2,800 guns, 400 tanks and over 800 aircraft were assembled to attack the German positions on the higher ground on the left bank of the Meuse river. Due to German resistance and supply issues, American progress was slow until the end of October 1918. The US Army incurred 117,000 casualties during this operation, including 26,000 dead.

More information:

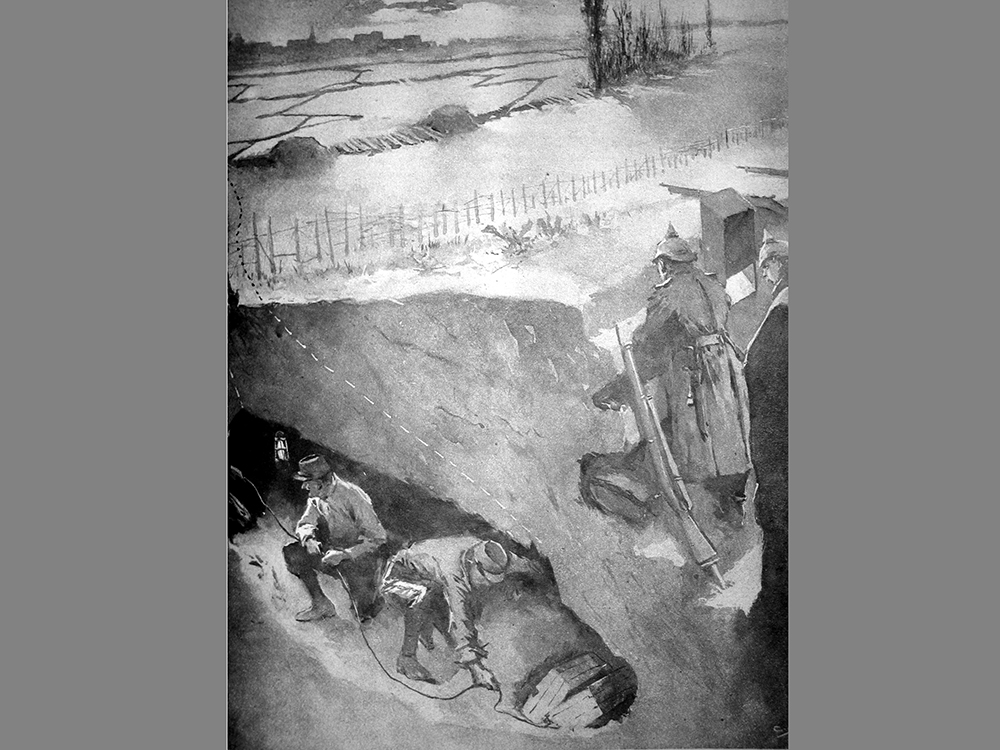

Mine warfare was employed on all parts of the Front during the war. In the Meuse area, there are several famous locations where this form of war left an indelible mark on the landscape.

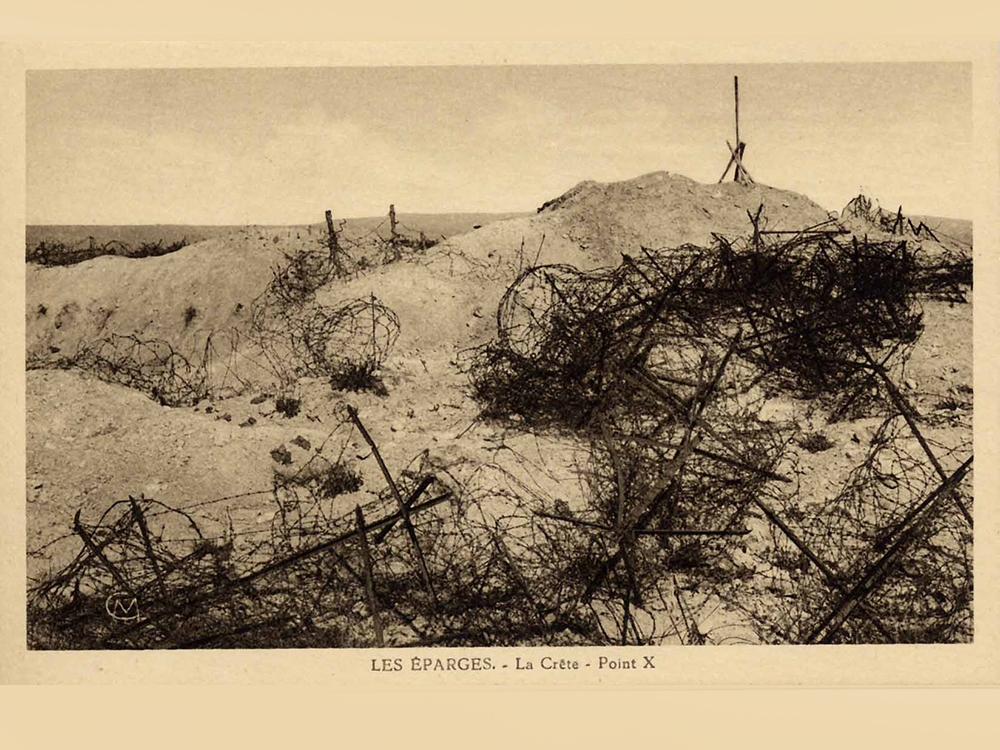

For instance, in the Argonne, the butte de Vauquois has been completely eviscerated by the explosion of 519 mines and camouflets (counter mines), all dating from between spring 1915 and April 1918. The largest mine, packed with 60 tons of Westfalit explosive, was set off on May 14th 1916, killing 108 French soldiers. On the high ground above the Meuse River, the crête des Éparges ridge witnessed one of the longest-running episodes of mine warfare in the history of humankind. Almost 130 mines and counter mines were set off, completely reshaping the face of the heights between February 1915 and August 1918.

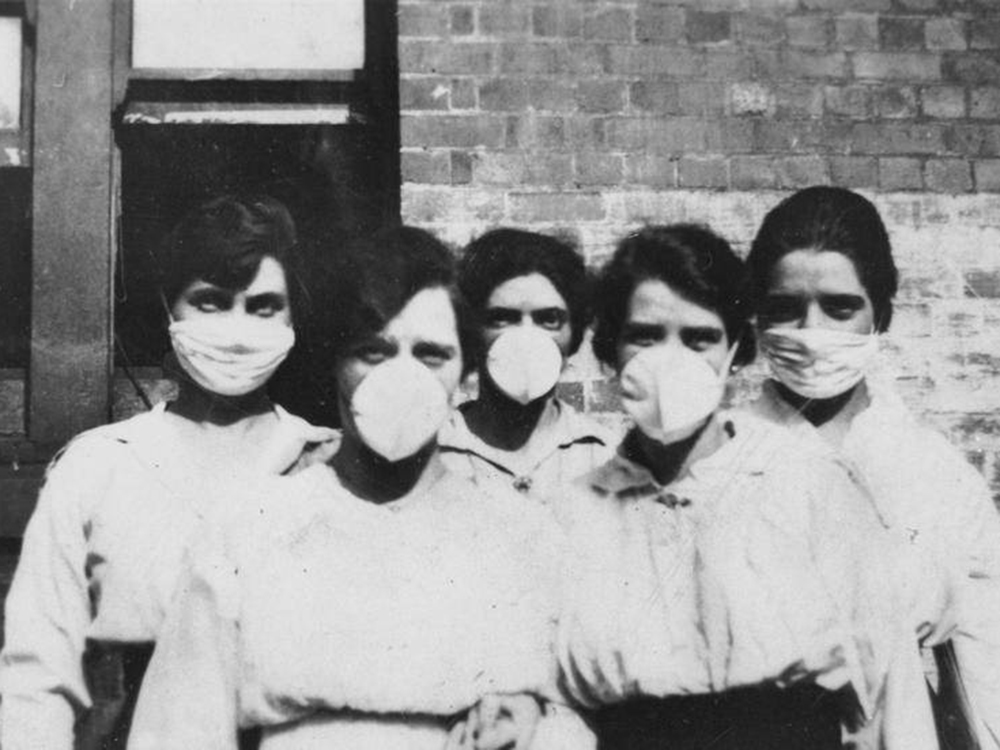

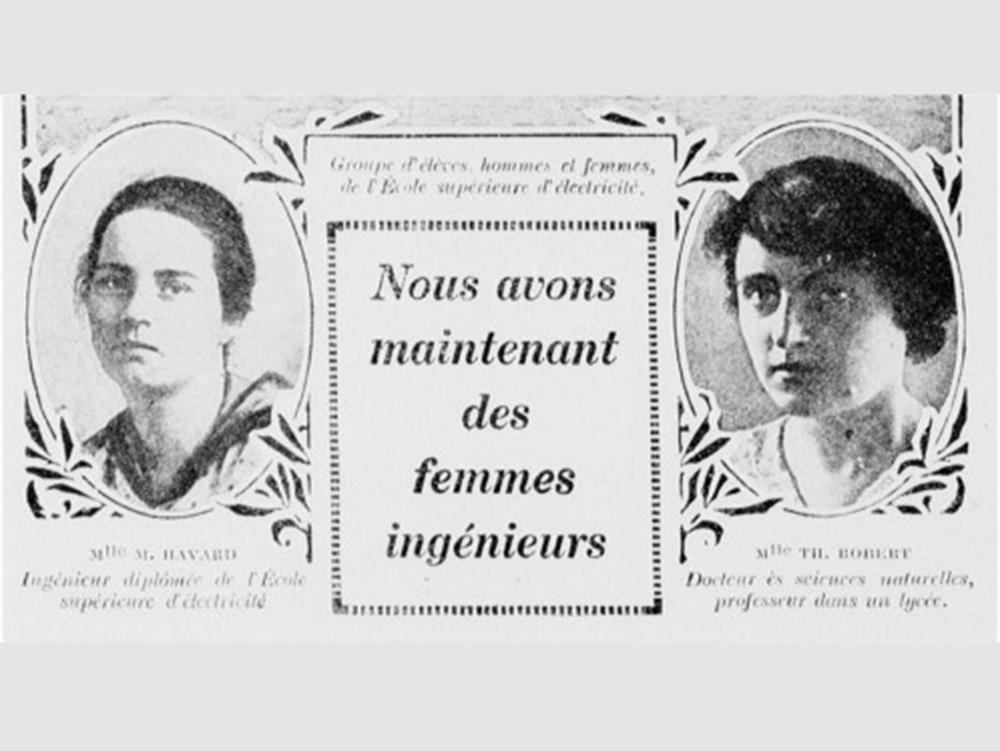

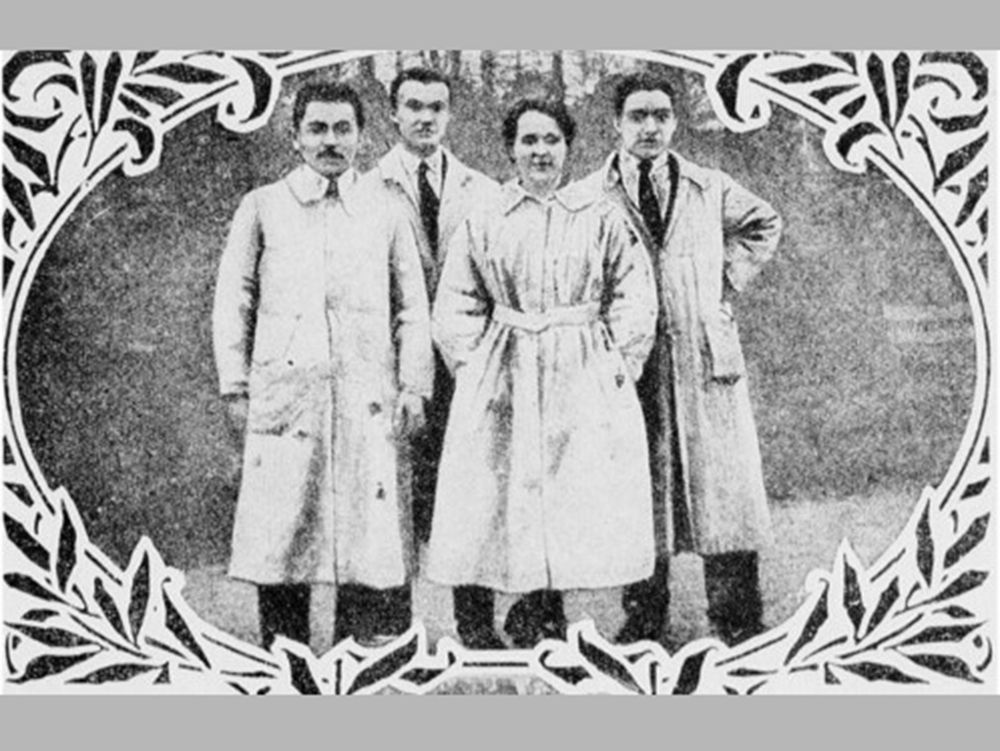

The war saw the call-up of millions of men all over Europe, especially in France and Germany, where entire generations were recruited. Faced with this situation, the needs of industry nationwide and the enthusiasm of female applicants, once the war had ended, engineering schools began accepting women onto courses that would have generally been perceived as the preserve of men.

In 1917, the Ecole Central de Paris accepted women for the first time, followed by the Institut national d’agronomie (1919), the Ecole Supérieure d’électricité (1919) and the Ecole de chimie de Paris (1919). In Belgium, the first female engineering student graduated from the University of Ghent in 1924.

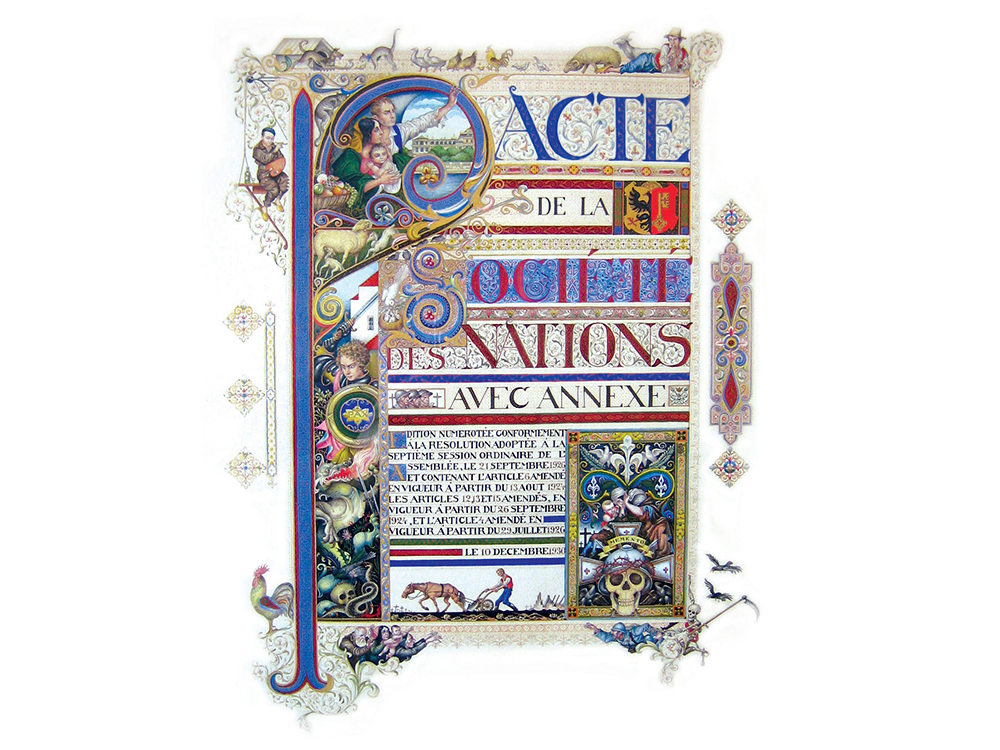

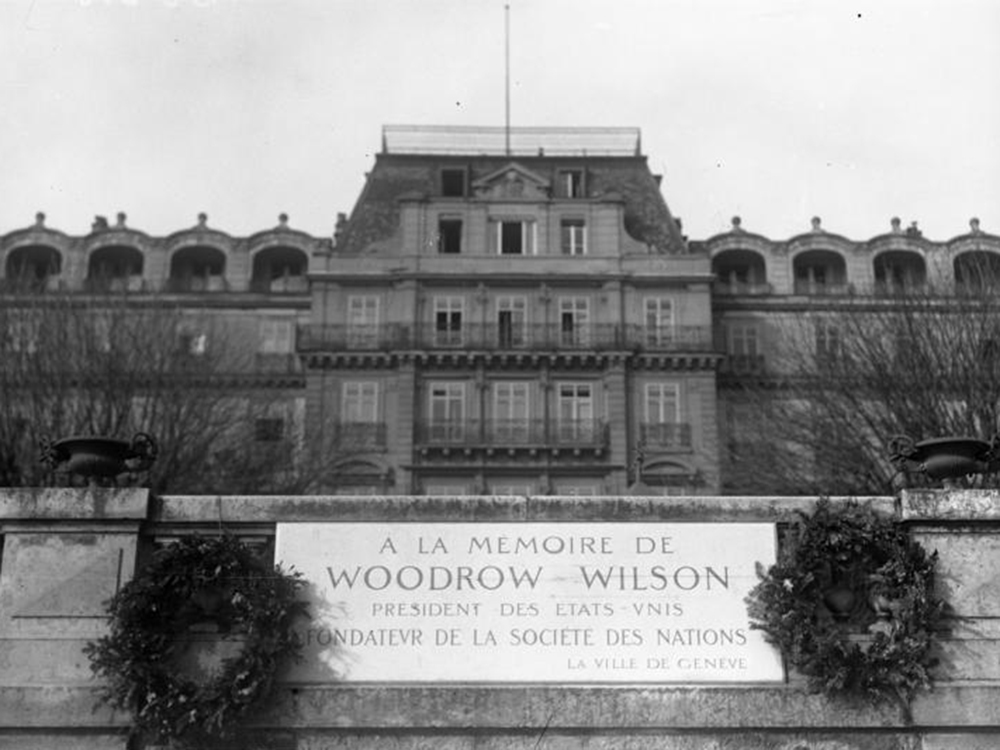

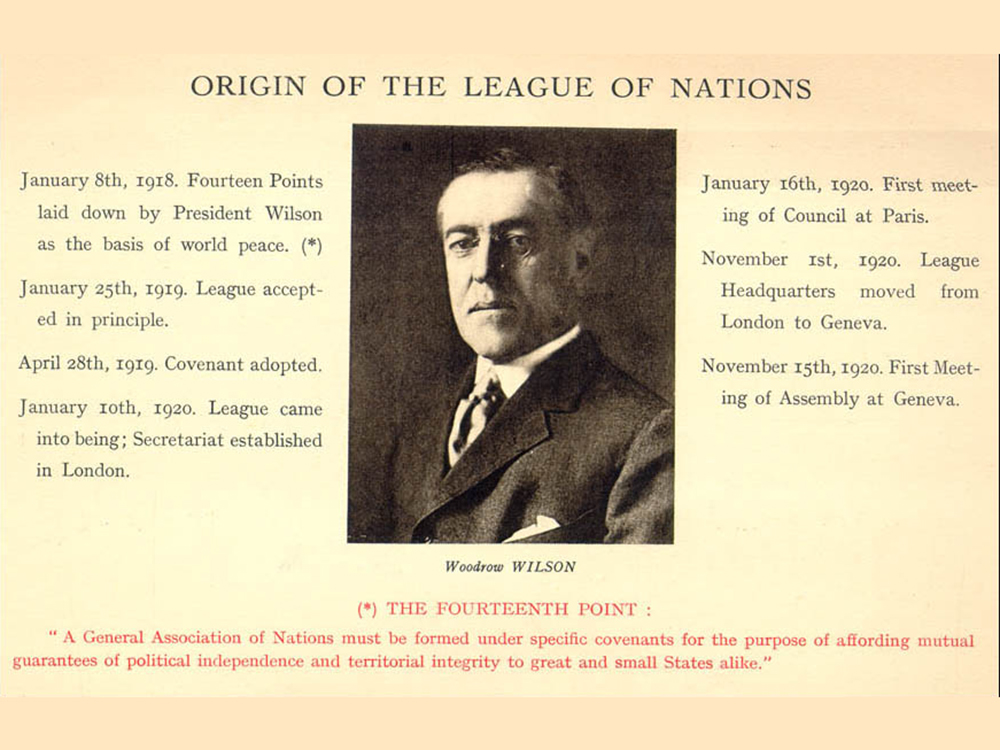

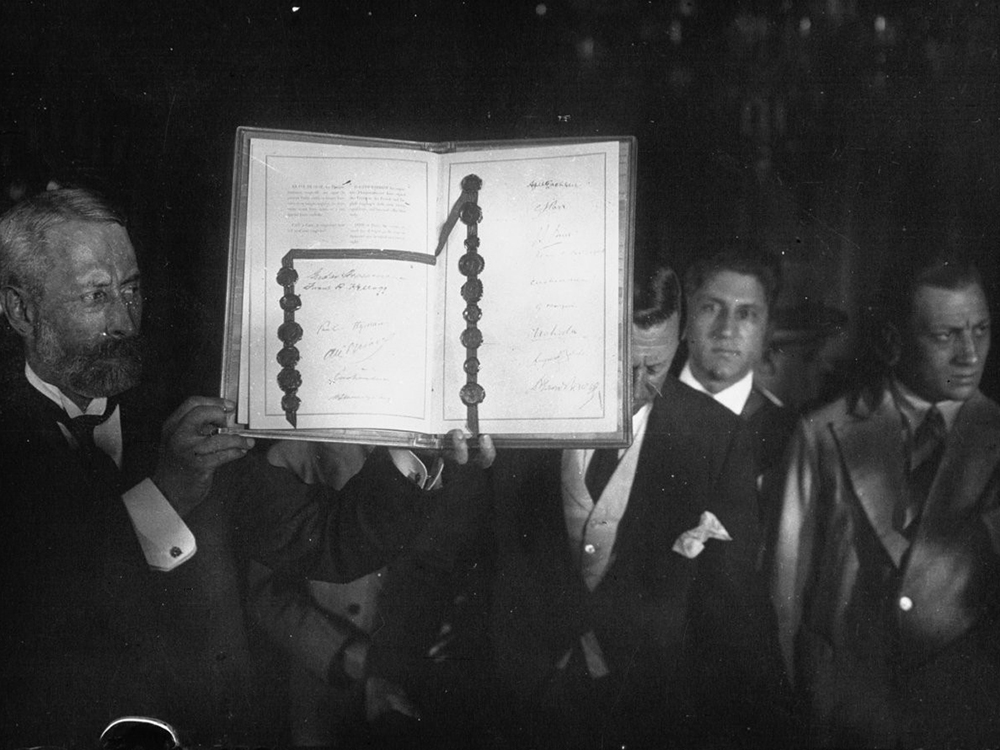

Founded in January 1920 after the signing of the Treaty of Versailles, the League of Nations (LoN) was an international body designed to come up with peaceful ways of resolving international disagreements through a system of arbitration and collective sanctions imposed on aggressors. Promoted by US President Woodrow Wilson, this approach was designed to encourage open negotiation rather than secret diplomacy.

However, the LoN had no armed forces of its own and little real dissuasive capacity, depending wholly on the cooperation of the Great Powers to enforce its resolutions. In spite of some notable successes, the League of Nations was unable to prevent aggressive actions carried out by the Axis powers (Germany, Italy and Japan) in the 1930s.

The millions of deaths and enormous material destruction of the Great War represented an immensely traumatic experience for Europeans. It was often said this war was the ‘War to end all Wars’. Scarred by the nightmare they’d lived and very aware of the continent’s relative decline in the face of Russia and the USA, men and women from a wide range of backgrounds sought to build the foundations of a system of European cooperation which could establish a long-term peace between old foes.

Various ideas and initiatives emerged, from the exercise of limited cooperation to the formation of much closer ties, in both economic and political spheres. The most famous of these were the 1924 Dawes Plan, the Locarno Pact and the French Committee for European Cooperation.

In the inter-war period, both France and Belgium developed systems of fortifications designed to reinforce their defences, especially along their borders with Germany.

In France, the Maginot line (built between 1928 and 1940), was a huge defensive network that ran from the Channel to the Mediterranean. Along the Franco-German border, the line comprised an almost continuous series of concrete and steel fortifications, barbed wire and artillery and machine-gun emplacements that were aimed at slowing a sudden enemy attack, winning sufficient time for full mobilization to take place.

In Belgium, Minister of Defence Albert Devèze launched the construction of a network of concrete pillboxes in 1933. These were fitted with guns and designed to secure the country’s eastern border in the provinces of Liège and Luxembourg.

At the same time, the Germans were constructing the Siegfried Line or ‘Westwall’. This stretched from the Netherlands to the Swiss border for over 630 km, thus covering virtually all of Germany’s western border.

More information:

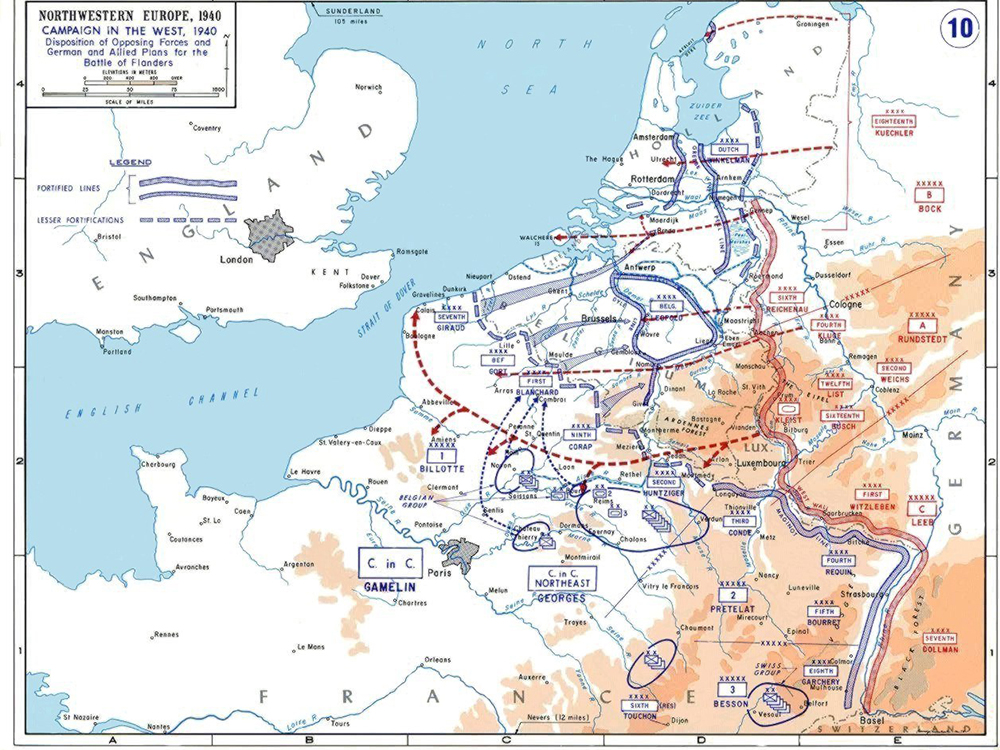

On May 10th 1940, Hitler’s armoured units launched a surprise attack on Luxembourg, the Netherlands and Belgium. Their objective was to advance quickly into France and avoid the defences of the Maginot Line. In three days, despite the valiant efforts of Belgian and Dutch troops, German troops, supported by heavy aerial bombing, reached the Meuse River at several points, including Sedan in France and Dinant in Belgium.

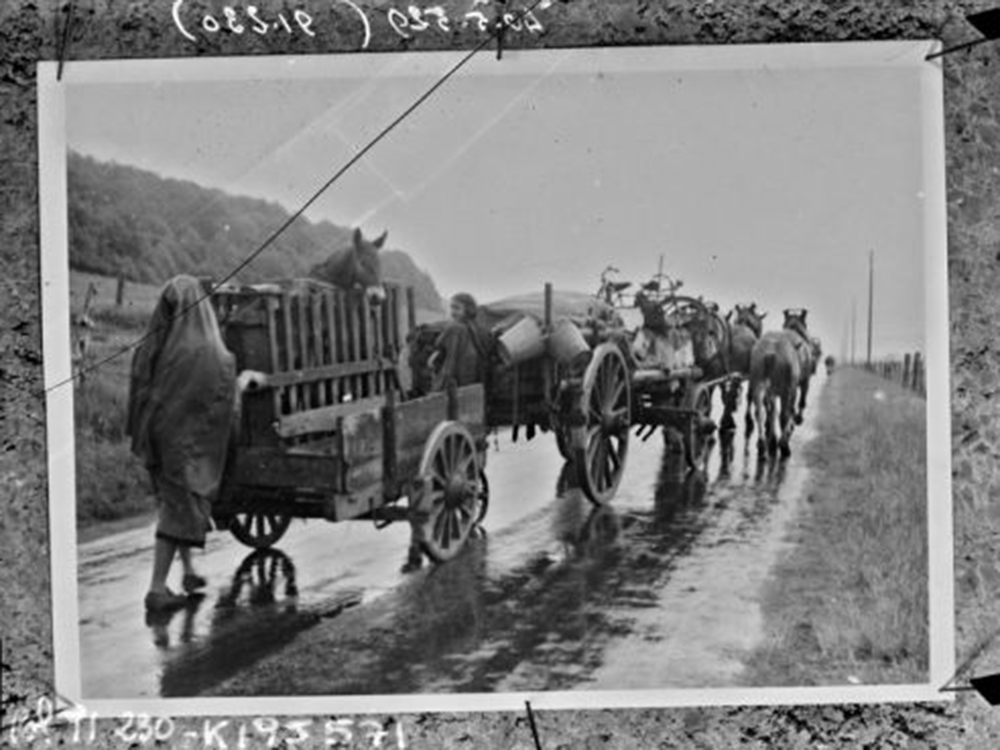

As part of the planning for this surprise attack, 500,000 German civilians were evacuated from border areas towards safer regions such as Franconia, Thuringia and Hesse. The advance of German troops resulted in a huge exodus of Belgian, Dutch, Luxembourgish and French civilians fleeing the fighting, haunted by the memory of 1914 and frequently mixed up with columns of retreating troops, all the while coming under attack from German bombers.

Eight to ten million civilians took to the roads, fleeing mostly towards Paris and the southwest of France.

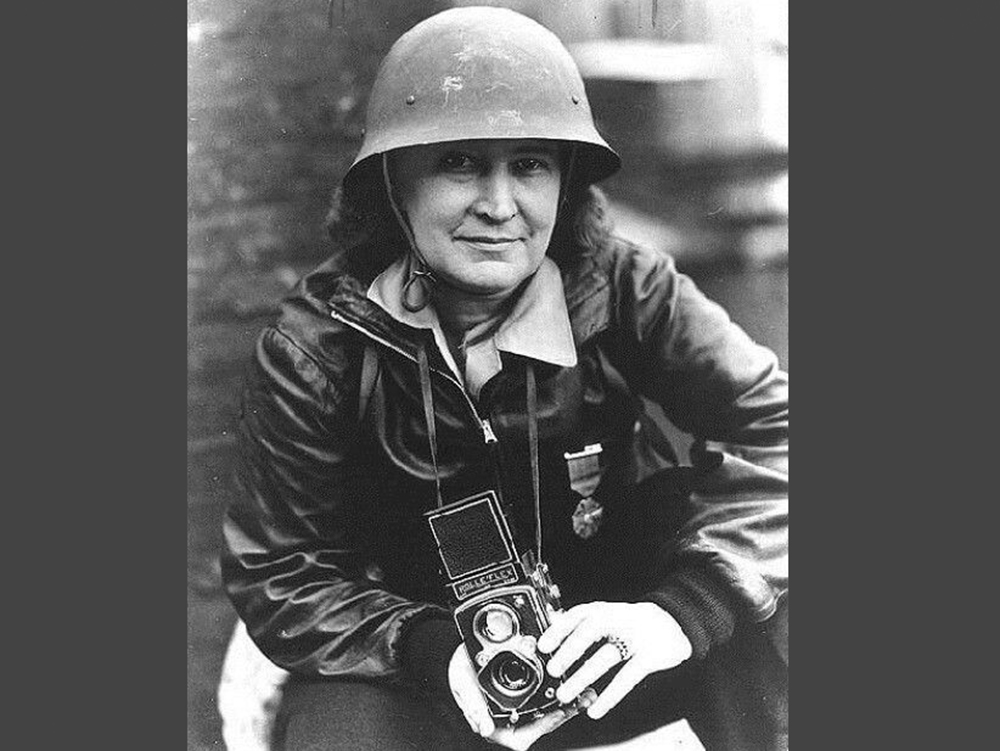

The Great War was for the most part covered by the military media corps. WW2, however, was reported on by many journalists and war reporters from all over the world. Many women distinguished themselves in this field.

There were almost 120 accredited woman reporters during the war, drawn from the four corners of the earth – the Soviet Union, France, Greece, Finland, the Netherlands, Norway, the USA and even South Africa.

Some of them became media stars in their own right, such as Margaret Bourke-White in her trademark flying jacket and Lee MIller. Both were American photographers and they covered the fighting in North Africa, Italy, France and the Ardennes. In 1944-45, from June to December, Martha Gellhorn (accompanied by Ernest Hemingway) and above all, Iris Carpenter and Lee Carson (nicknamed the prettiest girl in the Battle of the Bulge), reported on the latest developments from the sharpest end of the bloody battles of Normandy, Hürtgen and the Ardennes. Unfazed by the conventions of the time, these female reporters held their own in a world dominated by (sometimes very sexist) men, taking advantage of the increasing open-mindedness of US society.

As winter 1944 approached, German troops were falling back everywhere, but on 16th December Hitler launched a surprise attack in the Belgian and Luxembourgish Ardennes with a view to breaking through the Allied lines and reaching the port of Antwerp from where reinforcements and supplies were transported. At 5am, a rain of fire descended upon the US outposts in the Ardennes. Soon after, infantry and armoured columns launched their attack.

Houffalize (BE), La Roche (BE), Saint-Vith (BE), Hosingen (LU), Wiltz (LU) and Berlé (LU) are just some of the many villages which were largely destroyed. Several massacres occurred, including the Malmedy massacre. By December 22nd, Bastogne was surrounded, but the German army no longer had the resources to attain its goals. The 200,000 German soldiers mobilized for the offensive, supported by 600 tanks, never reached their objective (largely due to lack of fuel) and were stopped and then driven back by the Allies.

Hitler’s last offensive is a failure.

More information:

Bastogne was a major communications hub in the Ardennes, meaning that it was a key objective both in the Allies’ attempt to reconquer occupied areas and for the Germans as they tried to break through US and British lines in December 1944. Warned about the Nazi attack on December 17th, the US parachutists of the 101st Airborne Division were urgently dispatched to the area around Bastogne to stop the advance of German troops and defend the main roads leading into and out of the town.

Meanwhile, German armour bypassed the town to the north and the south. Bastogne and its defenders were surrounded. Just when the spearhead of the attack is halted outside Dinant, Hitler’s military staff decided to focus the ‘main effort’ on taking Bastogne. For nearly 3 weeks, in the cold and the snow, the town was under siege, its inhabitants hiding in cellars and shelters.

Cut off from their rear bases, the US soldiers held their positions despite the ferocity of the attacks until relieved by General Patton’s tanks, which then continued the offensive towards the German border.

On December 26th 1944, General Patton’s Third US Army entered the besieged town of Bastogne. The ‘Yankee’ 26th Infantry Division was sent to break through the ring of encircling German forces at the Schumannseck crossroads, enabling them to take the German troops to the east of Bastogne in the rear. The fighting was extremely fierce and American forces didn’t reach Schumannseck until 30th December. The advance was once again halted by the tenacity of the German defenders, who were dug in in the woods.

The front stablized here and for more than 3 weeks the fighting raged, with successive American attacks followed by German counter attacks in the snowy Ardennes forest. Deaths ran into thousands, inflicted by way of hand-to-hand combat, machine-gun fire and artillery shelling.

After the Harlange pocket was cleared (leading to the surrender of almost the entire German 5th Parachute Division), it wasn’t until the 21st January 1945 that the town of Wiltz was liberated and the fighting around the Schumannseck area was finally over. This fighting was the deadliest to be experienced in Luxembourg and in terms of tactics and the concentration of casualties, was reminiscent of the war of attrition of 1914 to 1918.

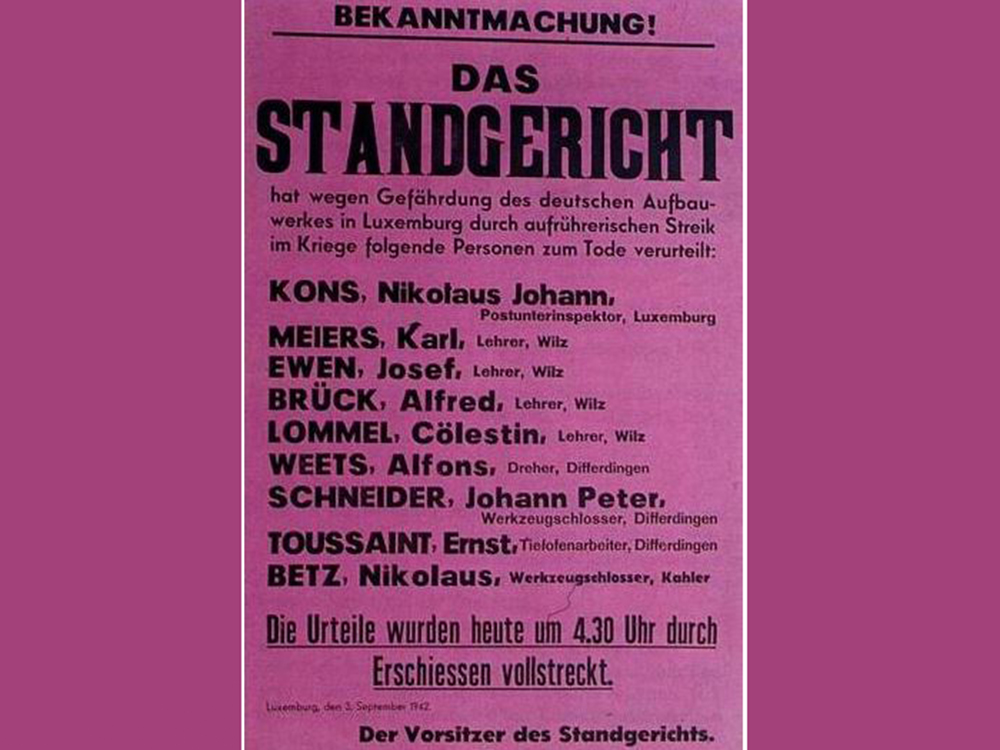

The German occupation put an abrupt end to Luxembourg’s independence. In July-August 1940, the Grand-Duchy was placed directly under German rule and the entire apparatus of the Luxembourg state was swept away. An intensive propaganda campaign orchestrated by the occupiers tried to convince Luxembourgers to support the Nazi regime. With the exception of a few collaborators, the inhabitants of Luxembourg never did so.

On the contrary, the longer the occupation went on, the more the Nazis tried to eradicate Luxembourgish national identity and the more the Luxembourg resistance to German rule increased. In 1941, a dozen or so independently-operating resistance networks were founded to fight the occupying forces. They helped political refugees to flee, supported those who tried to avoid compulsory labour and conscription after it was introduced in the summer of 1942, successfully coordinated a general strike and more.

However, active resistance would have been much less successful were it not for the support of the general public. Some extremely courageous patriots made their way abroad to join the Allied forces, thus contributing to their liberation of their country.

From January 1943 onwards, following the Casablanca Conference, at a time when Hitler’s troops were falling back on multiple fronts, the order was given to the British and US airforces to carry out the ‘progressive destruction and dislocation of the German military, industrial and economic system and the undermining of the morale of the German people to a point where their capacity for armed resistance is fatally weakened.

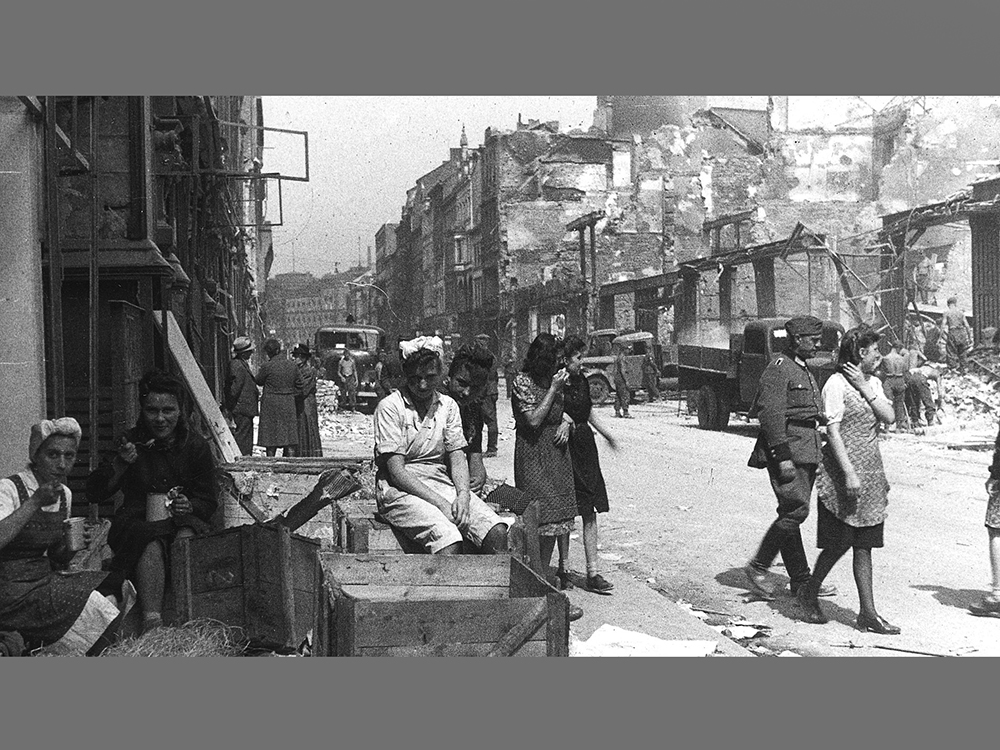

Massive bombing campaigns were organized by the USAAF and the RAF against German industrial areas, especially the Ruhr, followed by attacks on cities like Hamburg, Kassel, Pforzheim, Dresden and Mainz, which were almost entirely destroyed.

Saarbrücken was bombed extensively between 1942 and 1945, leading to the destruction of almost the entire old town and around 11,000 buildings, as well as the deaths of almost 1,200 people.

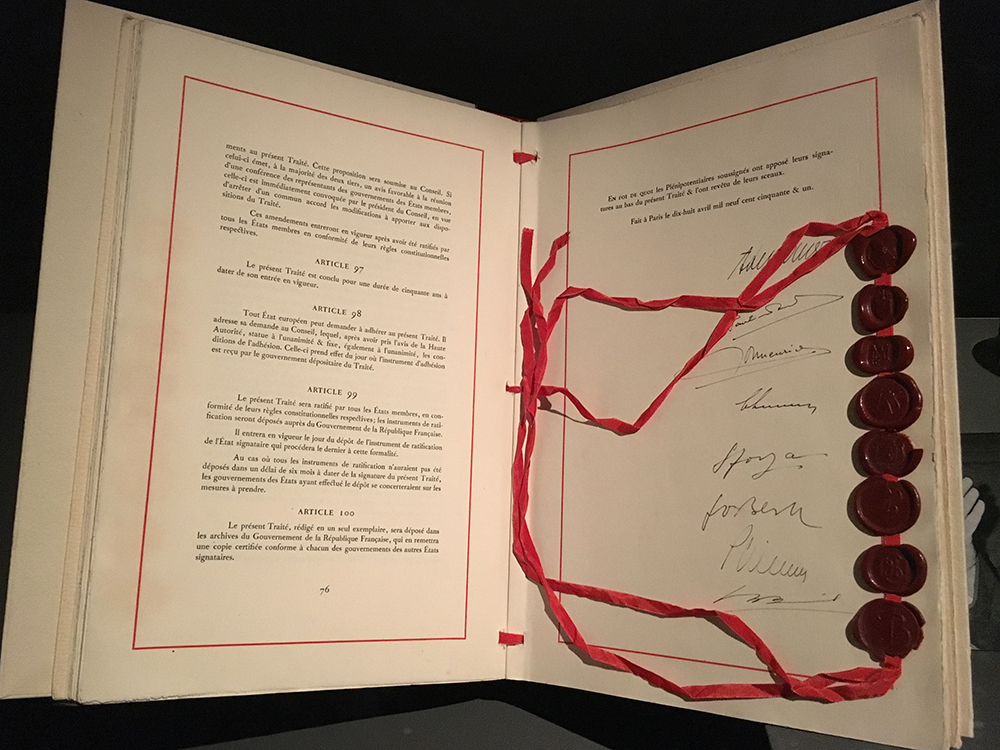

In the years after the end of the war, many Europeans were passionate about creating the political conditions for a partnership between France and Germany in order to avoid another war on the continent.

It’s against this backdrop that, on May 9th 1950, Robert Schuman, the French Foreign Minister, proposed the creation of a pan-European body that would create a common market between France and Germany for two of the key industries at that time, coal and steel. This had one main goal: to ‘make war not only unthinkable, but materially impossible’.

Inspired by Jean Monnet, the first director of the French strategic economic planning body, the CGP, this foundational text was a key ingredient in building a new Europe. It resulted in the signing of the Treaty of Paris on 18th April 1951 founding the European Steel and Coal Community comprising six European countries – France, the Federal Republic of Germany, Italy, Belgium, Luxembourg and the Netherlands.

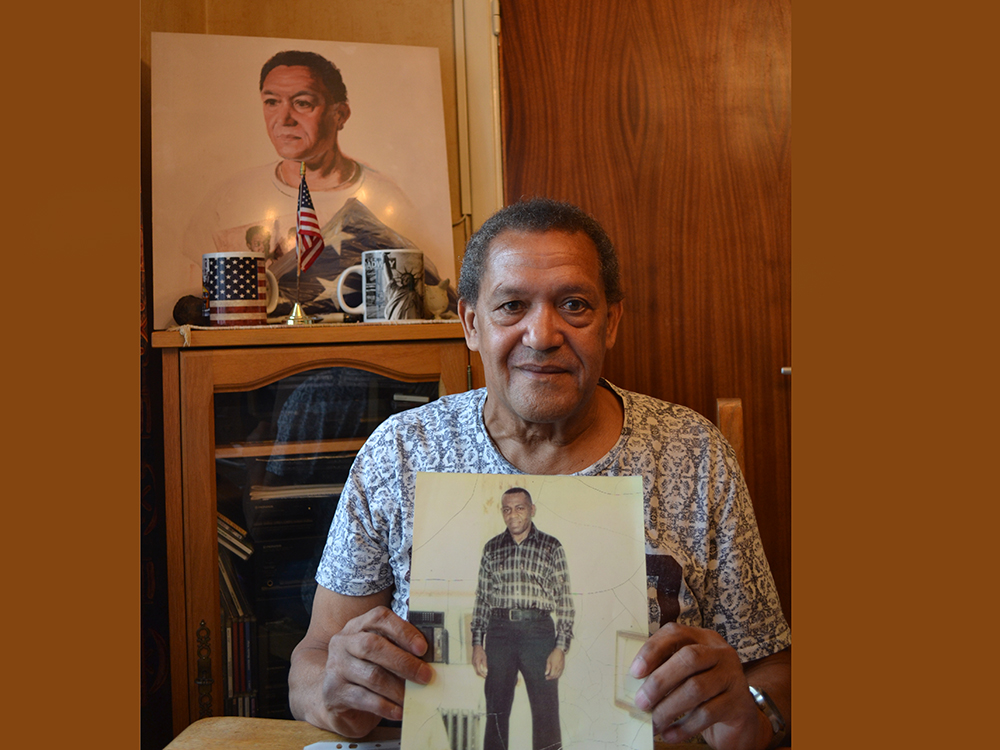

Recent research has been carried out into a little-studied subject – the way in which the inevitable chaos, brutality and social dislocation of war impacts every aspect of familiy life. These studies focus on stories of couples torn apart, women subjected to violence, absence and death (through the analysis of letters). Some researchers look at the topic of ‘war children’, born during or shortly after war – children born to enemy soldiers, whether through love matches or rape, children of women who had German partners or partners who were Allied soldiers (including ethnic minority soldiers). There is also the story of the children of prisoners and forced labourers in Germany.

These so-called ‘war children’ were treated like a shameful family secret, a heavy veil of silence hanging over them. Some were abandoned and others the target of resentment, racist remarks and bullying – some were even murdered. Many of these children strove to uncover their real identity, a difficult task often dependent on finding a letter that had been hidden away or a ‘forgotten’ photograph. Other resources were examined – oral and written accounts, which are now increasingly recorded in digital format, such as registers of births, marriages and deaths; military censuses and military service records, including records of death; documentaries and interviews with eyewitnesses etc.

Lastly, international organizations like the Born Of War international network and appeals on social media represent another avenue of research.

Furthermore, a multidisciplinary approach (drawing on archaeology, anthropology and genetics-based identification) to the recently-discovered bodies of soldiers makes it easier to reveal their true identity and story through the objects found with them (jacket buttons, dog tags, engraved bracelets and watches etc), molecular analysis (old DNA) of bones, teeth and hair and even their orodental status.